AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

An Essay requires independent thinking and the development of an argument supported by clear and logical ideas (Nesi and Gardner, 2012, p. 91). The essay can be developed in different ways, including analysis, evaluation and synthesis of perspectives, theories and research, application of definitions, theories and frameworks to examples and vice versa, arguing against opposing views, explaining cause and effect, comparing and contrasting, classifying, and other ways of building and supporting a position. 3 types of essay are found in AWA: Analysis Essay, Argument Essay and Discussion Essay.

Title: A Great Leader's Burden: Balancing Reason and Passion

|

Copyright: Rachel Matela

|

Description: From the selection of essays and excerpts from works relevant to the historical moment in which the plays on our course are situated... traversing various contemporary social, political and cultural debates... Choose ONE article as the basis for a discussion of the way its contents reflect or 'speak to' concerns raised in TWO plays on the course. You may choose to narrow the scope of your discussion to its application to certain types of characters, or you may wish to argue a contrary position to that posed by the article. You will be marked on your ability to mount and sustain a lively discussion, on the perceptiveness of your observations of the article and plays, and on the structure and coherence of your essay. Essay is written on: Thomas Wright, 'What we understand by Passions and Affections', The Passions of the Mind in General.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

A Great Leader's Burden: Balancing Reason and Passion

|

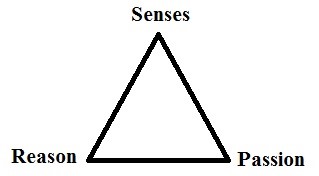

There is a famous Aristotelian belief that what sets man apart from animals and other living creatures is our inherent ability to make rational decisions, applying our developed faculties to intellectual enterprises and using them to think through situations from a logical perspective. In his essay, “What we understand by Passions and Affections,” Thomas Wright seems to take Aristotle’s side of this philosophical argument and calls this species-unique ability “reason” and what rebels against it “passions and affections”. However, he also insists that passions and affections are inherent in humans as well as reason “for all the time of our childhood and infancy” and that they are “common with us and beasts.” Human as we are, the mere possession of reason does not necessarily equate to its constant application in all matters of life, and often yielding to our passions is considered a failure to control our vices, or succumbing to sin. Two very interesting and complex characters that embody this internal battle of balancing reason and passion are Antony from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (1606), and the Duchess from John Webster’s Duchess of Malfi (1612-1613). This essay will explore the characters’ own manifestations of reason and passion and the challenges presented by this uniquely human struggle, but more specifically their struggles as people of power and leadership and the inevitable pressure to rule with godlike virtue, just as this right is supposedly given to rulers by God. First, I would like to take Wright’s three main concepts (reason, passion and the senses) and make a visual representation of his proposed relationship of these concepts.

Wright suggests both reason and passion serve the senses but in different ways, so a triangle with senses at the top and the other two at the sides seems the appropriate visual representation. Reason and passion may be separate but they are still connected, for according to Wright, “passions stand so confined with sense and reason that for the friendship they bear to the one they draw the other [i.e. senses] to be their mate and companion.” I shall use this image of a triangle throughout this essay to relate these concepts to each other as well as to help describe Antony and Malfi’s struggles with the three aforementioned concepts. Additionally, to narrow the scope this analysis will deal particularly with their struggles with a specific kind of passion, i.e. lust, and how it compromises their character as powerful nobility. In both plays, lust is treated negatively as something that mars the main character. So it is also in Wright’s essay where he writes: “We have a continual and molestful battle with carnal vices and worldly enticements.” We will then further analyse how both Antony and Malfi try and use their reason to not just combat and control their passions, but also to excel in their own ways as complex characters who are likeable in the dignity and humanity that they manage to display even in the direst of situations. It is appropriate to begin this analysis with the character that perhaps more outwardly exhibits the symptoms of passion: Mark Antony. A noble leader and a great soldier, he is famous and respected for his military prowess and bravery. However, from the opening scene we are told of his flaw – his own friend and subordinate Philo begins the play by expressing his fear that Antony, one of the three mighty pillars of the Roman Empire, has diminished himself and “transform’d / Into a strumpet’s fool.”[1] This hero’s tragic trait from the outset is defined as his lust for the exotic Cleopatra, the queen of ancient Egypt, as he submits himself to her and the pleasure she provides. This is Antony’s triangle: the great warrior-general Antony on the side of reason, and love-struck Antony on the side of passions. Antony’s symptoms of lust are mostly congruent with Wright’s points. In the first scene, we learn that he has a wife back in Rome who he seems to have completely abandoned, as he nonchalantly dismisses a messenger from Rome. This matches Wright’s argument that these perturbations “corrupt the judgement and seduce the will”. Antony’s passions certainly rebel against reason when he immediately goes back to Cleopatra after hearing of Caesar’s betrayal, even though he has just married another woman, Caesar’s sister Octavia. Despite his honour and bravery as a general, he forfeits his battle against Caesar the moment Cleopatra’s ships retreat, and readily admits to her, “How much you were my conqueror, and that / My sword, made weak by my affection, would / Obey it on all cause.” (III.12.65-67) However, Antony’s nobility as a leader, his leg of reason, is not neglected in the play. In I.2 when he finally listens to the messenger in the absence of Cleopatra and learns of his wife Fulvia’s death, this serves as a wake-up call for reason to resume control of his senses – Antony finally leaves Egypt to deal with Pompey and help Caesar subdue the pirates. He even goes so far as agreeing to marry Caesar’s sister for peace in II.2. As a general, he manages to negotiate a truce with Pompey, and he wins the naval battle at Alexandria against Caesar even though he is not particularly an expert in that field. He treats his subordinates benevolently, too: Antony blames only himself when Enobarbus betrays him, and when he’s convinced all hope is lost in winning the battle against Caesar, he bids his own men to leave him so he can take his life and die honourably. Antony keeps alternating between being a willing victim to his passions, and wanting to fulfil his duties as one of the great Roman leaders in an attempt to reconcile these two sides of him that really seems impossible to harmoniously co-exist. Caesar’s adamant decision of his death makes that clear – he refuses to let Antony live peacefully in Egypt or be a mere citizen of Athens. The setting of the play itself reminds us of this: Rome is a representation of a cool, almost stoic mind-set that sharply contrasts the natural and passionate Alexandria. Antony repeatedly travels back and forth between these two cities and is stuck in between his allegiance to Caesar and his love for Cleopatra. His inability to juggle these two separate Antonies, these two separate ways of living, ultimately undoes him and those around him. The unnamed Duchess of Malfi goes through a similar ordeal. Although the play is mostly concerned about how her brothers try to control her after her first husband dies and the subsequent torture she has to endure at their hands, it is also about her challenging the stereotypical notion of a “wanton widow.” This concept suggests that because widows are no longer under direct patriarchal rule (particularly by their fathers or husbands), they are uncontrollable and lecherous. Her brothers Ferdinand and Cardinal try to convince her to remain chaste and to never remarry, and the former certainly likes to keep reminding the audience of the presumptions and preoccupations he has with his twin sister’s sexuality. Malfi decides to marry her steward Antonio secretly, however, instantly after she promises her brothers she would not, and her language when wooing him is quite forward and suggestive. “I do here put off all vain ceremony/ And only do appear to you a young widow/ That claims you for her husband; and like a widow, I use but half a blush in’t.”[2] Malfi is clearly sexually as well as emotionally attracted to Antonio, who is a poor match for her as he is so many levels below her station. As much as she submits to her passions in marrying whoever she well pleases, she remains aware of her political status and authority as The Duchess. We see this not only when she refers to herself as a prince or when she proclaims, “I am Duchess of Malfi still,” (IV.2.123) but also because she keeps her marriage with Antonio a secret. Malfi is conscious to the fact that submitting to her passions was not necessarily a very smart decision, considering she has broken down the rules of hierarchy. It is ironic then that Wright uses a princess figure to symbolise reason, as he writes, “Reason dependeth of no corporal subject, but as a Princess in her throne considereth the state of her kingdom,” which the Duchess, in her hasty marriage to her servant, has not done. Even her maidservant Cariola fears that her sovereign has gone mad when she says, “Whether the spirit of greatness or of woman / Reign most in her, I know not, but it shows / A fearful madness. I owe her much of pity.” (I.1.492-494) Malfi’s innate nobility, however, shines through most brilliantly when Ferdinand comes back to capture her and her family, and subsequently tries to torture her mind and soul in graphically horrific ways. She remains the paragon of sense, hope and strength, and does not lose her wits to Ferdinand’s control. Even when asked if she fears death, she says, “Who would be afraid on’t, / Knowing to meet such excellent company / In the’other world?” (IV.2.152-154). She accepts and welcomes her death nobly, even wishing to finally appease her brothers with her obedient blood after she has long disobeyed them. We can now readily perceive that both Antony and Malfi possess the characteristics of virtue and nobility that leaders and rulers ought to have, but the pressure of responsibility on the other side of the coin places them at an enormous risk. Malfi in her wooing scene to Antonio laments “the misery of [those] that are born great,” (I.1.432) – this does not only apply to the difficulty of procuring a mate, but also extends to the pressure of balancing their public and private lives, their passions for their lovers and their responsibility to rule righteously. The sense-passion-reason triangle is situated and largely encapsulated in a social world/context that, for political figures, further agitates and complicates this balance. The events in the plays also extend outside and into their immediate real-world social context of early modern England, where there was a clear preoccupation with the authority of a ruler. At the time both plays were written, King James I ruled England, and he used the “The Divine Right of Kings” as political backing. King James I believed that, through God’s grace, monarchs were essentially God’s representatives on earth. This strongly legitimated the hierarchical system as divine and final. Although our characters are not Kings, they are still considerably high up in the Great Chain of Beings. The plays seem to strongly contest this divine right to rule in that both leaders, Antony and Malfi, are subjected to Fortune’s wheel and fall tragically. They are, after all, not God and are merely humans, and as much as humans have the innate ability to think as Aristotle proposes, we also have the innate ability to submit to our passions just as beasts do. The impossibility of living purely as godly models of virtue, and society’s heavy expectations for them to fulfil such impossibility, is unjust towards them. Both plays make it a point to have the people around these two heroes continuously question or judge their leaders’ ability to rule. Philo is a prime example for Antony, but so is Caesar, when in I.4 he complains of Antoy’s debauchery in Alexandria to Lepidus and even goes so far as saying, “You shall find there / A man who is the abstract of all faults / That all men follow.” In the Duchess of Malfi, besides her unnaturally controlling brothers’ and Bosola’s constant admonitions and speeches that question greatness, two pilgrims in III.4 discuss Malfi’s sorry state and reflect on her decisions. Leaders and sovereignty simply cannot escape the judgement of both their friends and their subjects, and the political and public eye at large. There are those like Webster and Shakespeare who see the problem in this way of thinking and present it to the audience through these plays. Webster even writes in his dedication of the play to George Harding: “I do not altogether look up at your title, the ancientist nobility being but a relic of time past, and the truest honour indeed being for a man to confer honour on himself, which your learning strives to propagate and shall make you arrive at the dignity of a great example.” Leadership is not an easy role, especially under the inevitable duress of balancing reason and passion when there are so many other factors and circumstances outside the triangle that further complicate matters. Wright’s idea that “reasons straightways inventeth ten thousand sorts of new delights which the passions never could have imagined,” did not seem to sway both characters to manifest in both characters. Perhaps wanting glory and power warrants the sacrifice of personal happiness and satisfaction, or vice-versa. Nevertheless, the burden of responsibility simply cannot be ignored. Their struggle, although tragic, beautifully humanises Antony and Malfi in a way that highlights their difficult relationship with both reason and passion. It not only suggests the plays’ and the era’s preoccupations with greatness, inherent nobility and legitimacy to rule, but also reminds the audience that even heroes and aristocrats have unique personal struggles that ironically stem from this very greatness.

Bibliography Shakespeare, William. The Tragedy of Antony and Cleopatra, edited by A. R. Braunmuller. Penguin Books, 1999. Webster, John. The Duchess of Malfi 5th Edition, edited by Brian Gibbons. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.

[1] William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, ed. A. R. Braunmuller (Penguin Books), I.1.12-13. [2] John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi 5th Edition, ed. Brian Gibbons (Bloomsbury Publishing), I.1.446-448. |