AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

A Research Methods Report helps the writer learn the experimental procedures and the ways research findings are made in that discipline (Nesi & Gardner, 2012, p. 153). The question to be investigated is often provided as part of the assignment, and there is usually less focus on existing research and much more on the methods and results of the writer's own research. An IMRD (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) structure is often used. AWA Research Methods Reports include Experiment Reports, Field Reports and Lab Reports.

Title: Memorial Research Report

|

Copyright: Anonymous

|

Description: Investigate one memorial /commemorative structure from the list provided, and present your findings in a 2500 word report. Consider the theme of commemoration or memorialisation, and using a case study, examine the purpose and meaning of war memorials and how it is expressed through design, symbolism, and use of materials.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

Memorial Research Report

|

Abstract The purpose of this research is to attempt to investigate the purpose of memorials pertaining to the South African War. The memorial chosen to be investigated for this research report is the South African War Memorial located in Albert Park. The approach taken in this research are through physical observations of the memorial itself, research from primary and secondary sources, and observing photographs taken by the author as well as historical photographs. The key findings made in this research report is that the South African War, despite it being a small-scale war, was significant in shaping New Zealand’s national sense of pride and belonging.

Introduction Memorialisation in general, is seen as a way to remember past events in the form of physical representations (Gurler & Ozer 2012). These physical representations of past events can be in the form of statues, obelisks or even architecture (Gurler & Ozer 2012). They are also often strategically placed in public areas, with the intention of reminding the public about how the horrors of war has affected them whether directly or indirectly (Gurler & Ozer 2012). In New Zealand, public memorials and especially war memorials serve as a way to communicate national pride as well as to express sorrow for the men who have lost their lives (Inglis & Philips 1991). The war memorial that I have chosen to focus on in this research report is the South African War Memorial located in Albert Park. The South African War, though not as celebrated to the same degree as the First and Second World War, remains an important part of New Zealand history in terms of its values and its significance to the nation. To attempt to examine the purpose and meaning of the war memorial, the methodology used to investigate is through physical observations, photographs and library along with online research of both primary and secondary sources. Other observations that may be of relevance may also be mentioned.

Description The South African War Memorial is located on Albert Park, part of Auckland Central. Since the First World War, parks and gardens became known as ‘living memorials’ (Historic England, 2015). This is because it provided those with connections to the war at the time with a space of remembrance (Historic England, 2015). The war memorial was erected by members of the 5th contingent to honour their comrades who have fallen in the South African War (Philips, 2016). The memorial was unveiled in 1902 by R.J. Seddon, Premier of New Zealand (PapersPast, 1902). During the unveiling ceremony, the military attended to both welcome home the comrades as well as to lend a helping hand at the ceremony (PapersPast, 1902).

Figure 1: Google Earth screenshot of Albert Park. Retrieved from Google Earth (2018).

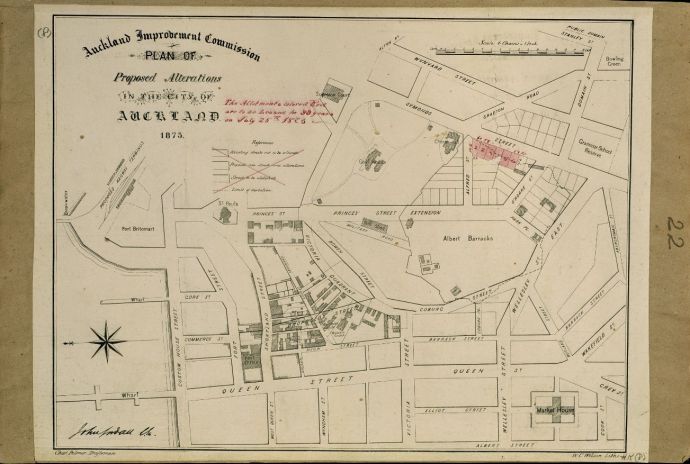

Figure 2: Auckland Improvement Commission plan of proposed alterations in the City of Auckland, 1873. Retrieved from Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, NZ Map 4475-22. No known copyright. As seen in Figure 1, Albert Park is at the heart of the University of Auckland’s city campus with the Auckland Art Gallery just a walking distance away. Trees cover most of the park, providing shade for the public. There is a gazebo in the far left of the picture and a fountain in the far right located in an open area. This is in large contrast to Albert Park in the late 1800s. As seen in Figure 2, Albert Park was once a military barrack and may have had less greenery than the park present day. Figure 3: The Troopers’ Memorial, Albert Park, Auckland Domain, including statue and cannons. Retrieved from Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/30658574. Unknown copyright. The curtilage or the surrounding area on which the war memorial stands appears to have changed since the time it was erected. From Figure 3 above, three war cannons are placed around the war memorial and this may have had a reason. Furthermore, the area on which the war cannons and the memorial are placed on is fenced off. Based on personal observation, it could be placed as a sign of no entry and only for viewing or to give the image of the soldier triumphant amidst the carnage.

However, as seen in Figure 4 above, the current landscape has changed quite a fair bit. The cannons are still part of the curtilage around the war memorial though with one cannon missing. The area is no longer cordoned off by fences with the exception of the memorial and it is instead now fully open to the public as Albert Park is now a public space managed by Auckland Council (Heritage New Zealand, 2018). Also, comparing Figure 4 to Figure 3, there is far more greenery in the current landscape. This could be that Albert Park was once the site of a military barrack, which may have required extensive clearing of the landscape. Upon physical observation, the focal point of the South African War Memorial is a statue of a life-sized soldier that appears to be carved out of marble. This is confirmed in primary research, where it was stated in the Ashburton Guardian in 1902 that the statue was carved out of marble (PapersPast, 1902a). It is said that this is because imperial tributes were mostly carved and with regards to the larger memorial designs, they were mostly carved by Italian craftsmen instead of members of the British Empire (Philips, 2016). However, no primary research has been found to prove this statement. The soldier’s right hand rests atop a small cannon while the left hand appears to be holding a sword as well as a package. Pertaining to his stance, he appears to be at ease and standing tall with his head held high. This is normal as most war memorials to the South African War with soldiers carved onto them tended to be in a relaxed position (Philips, 2016). Furthermore, the choice of the soldier to be part of the memorial could suggest a reflection of a sense of national pride or just general affluence of the New Zealand communities (Inglis & Philips, 1991). With regards to other features of the war memorial, a marble pillar is constructed behind the statue to prevent the structure from collapsing. Below the statue is a block-type structure that is also made of marble. There is also a carving of an open-mouthed creature that could be a gargoyle or lion below the inscriptions. However, no information from primary research can be found to truly confirm either claims.

Figure 5: South African War Memorial, Albert Park (author’s own, 2018) From Figure 5 above, the function of the open-mouthed creature appears to have been of a fountain. Through primary research, it is said that the pedestal below the statue served as a drinking fountain (PapersPast, 1902a). However, it is evident that it is no longer serving its purpose as the war memorial has been cordoned off by iron railings (Heritage New Zealand, 2018). The base of both the marble block and the statue itself appears to be made of cement render at first glance. However, after further research, a secondary source from Heritage New Zealand (2018) states that it is actually made of bluestone. Also, it is stated that changes to the memorial do not just include the railings but also the soldier’s head, left hand and sword. It is said to have been duly removed and replaced over the years (Heritage New Zealand, 2018). In spite of years of maintenance, the memorial appears to be in good condition.

Discussion Since ancient times, there has always been a need to remember past events and using space to house memories was one of them (Dimkovic, 2016). This need to remember has extended to modern times, where space is often used to house memories in the form of physical representations (Dimkovic, 2016). These physical representations are often in the form of memorials.

The most notable changes to the nature of memorialisation started with the First World War (Historic England, 2015). The war had a significant impact on the way memorials were viewed and this was largely due to the huge loss of lives in the war (Historic England, 2015). However, despite World War I memorials having much greater recognition, it was the South African War memorials that were said to have the most revealing memorials (Pawson, 1991). The memorials tended to be more triumphant in appearance but this was not because of the loss of lives (Pawson, 1991).

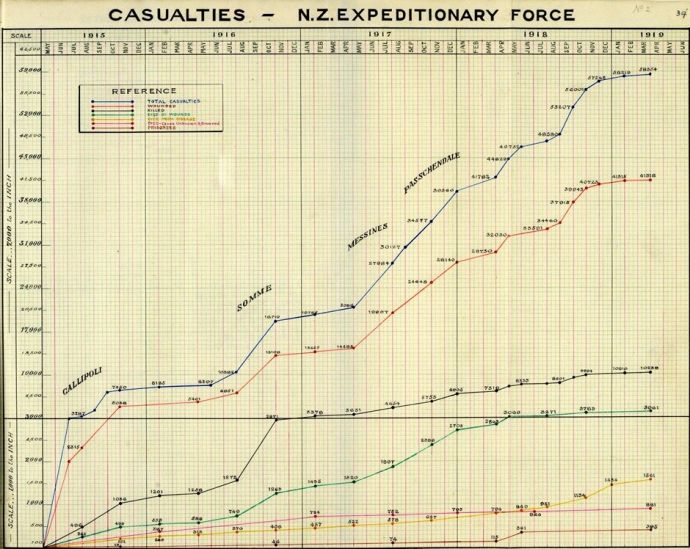

Figure 6: Graph of NZEF casualties, 1915 – 1919. Retrieved from NZ History, drawn by the Defence Department’s Base Records Branch in 1919. Unknown copyright. According to Figure 6, the blue lines show that there were approximately over 50000 casualties within the New Zealand Expeditionary Force serving in the First World War. In contrast to that, there were only 6500 volunteers in the South African War. Casualties only amounted up to 3.5% of the total volunteers with about 166 wounded (Philips, 2016). This may not be true as information from primary research mentions casualties from all contingents from different countries. With that said, the number of casualties may be higher or lower. Nevertheless, it can be derived from this information that though the South African War played a small part in New Zealand’s national and military history, the memorials erected in tribute to them played a much bigger part than just remembrance. With regards to remembrance, the memorials erected for the South African War tended to be commissioned by friends, family or close friends (Philips, 2016). However, there were exceptions to this because even surviving soldiers from the war will occasionally commission to build a memorial (Philips, 2016). Furthermore, details of how the fallen soldiers lost their lives tended to be more informative. In the case of the South African War Memorial at Albert Park, the unveiling saw Lieutenant J.T. Bosworth describing the manner of each soldier volunteer’s death in great detail (Philips, 2016). However, the main purpose of these memorials though were seen as a way to commemorate New Zealand’s contribution not only to the nation but also as a sign of loyalty to the British Empire (Pawson, 1991). In a way, the memorials were regarded as physical representations through which national pride is communicated through as well as to express deep condolences for the lives lost (Inglis & Philips, 1991). Public reception for the memorial mirrored the reception that of the surviving soldiers. When R.J. Seddon sailed from England to make his speech to the public during the erection of the South African War memorial, he emphasised New Zealand’s strength despite its small size and even compared the nation’s strength to cities in the United Kingdom (PapersPast, 1902). This comparison may have given New Zealand citizens a strong sense of pride, believing they were on equal footing with Britain (PapersPast, 1902).

Figure 7: South African War Memorial, Albert Park (author’s own, 2018) Eluding to the sense of national pride evoked by the South African War, the memorial at Albert Park as seen on Figure 7 can be used to further observe meanings attributed to the way it has been carved. From personal observation, a nature/culture binary can be seen in the way the memorial is carved and structured. For example, the intricately hand-carved design of the soldier may represent ‘culture’ which is then placed atop a rather plain-looking pedestal, which may represent ‘nature’. Also, symbols used in the memorial can also elude to hidden meanings. For example, from personal observation the creature in the front of the pedestal may serve as a symbol of the soldiers’ bravery amidst the ferocity of the war.

Figure 8: Canterbury nurses who served in the South African War. From left to right: Sisters Hiatt, Littlecott, Peter and Webster. Photographer identified. Retrieved from Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22687120 One observation from doing research of the memorial as well as observation of the memorial is that the participation of women in the South African War were not heavily emphasised if at all. It was recorded that there were seven New Zealand nurses who had served in the South African War (PapersPast, 1935). From Figure 8, it is likely that the four women were part of the seven nurses who had volunteered to serve. One of them was Sister Gradwell though she is not pictured in Figure 8 above. She was awarded a medal for serving in the South African War which totalled up to seven medals for her contribution to both World War I and the South African War (PapersPast, 1938). Therefore, there may also be a gendered narrative interwoven within the war. In the case of Maori, they did not serve as soldiers in the war as they were not allowed to since the South African War was considered a ‘white man’s war’ (Paterson, 2013). Regardless of this, some supported New Zealand’s involvement in the war, possibly as a way of gaining national identity and acceptance within a nation that has so suppressed them (Paterson, 2013). Much of the symbolism and meanings attributed to the South African War memorial in Albert Park has somewhat trickled down to present day though it is not felt as strongly. The memorial does not have much of a presence within its landscape as it did when it was first unveiled in 1902. The landscape surrounding the memorial in Albert Park is no longer to re-enact but rather, it has become more recreational as the park is now a public space. It has, in a way, fused into the urban background and is no longer considered an important part of the landscape. However, efforts to maintain its original significance can be seen through the cannons placed a few feet to the sides of the memorial. The absence of fences can be seen as a way for the public to interact with the surroundings and possibly understand the significance of the war to New Zealand. Regardless of whether this significance can be felt in present day, it must be acknowledged that memorials do not only serve as a form of remembrance but also as a form of pride.

Conclusion In conclusion, the South African War Memorial in Albert Park in physical terms had a lot of meanings attributed to it though it cannot be seen at first glance. As mentioned in the discussion, the war memorial seems to represent a culture and nature binary. This could then go on to emphasise the sense of national pride that is seen to be embedded into the war memorial. For example, the intricately carved soldier being the centre piece of the memorial showed a sense of pride that are felt through the citizens of New Zealand (Inglis & Philips, 1991). Furthermore, the landscape in which the memorial is placed in could have been a way to re-enact the war with the cannons placed on either side of the memorial just a few feet away. This can then extend to the notion that despite the small loss of lives in the South African War, great lengths are taken to ensure every detail is put not just in manner of the soldiers’ death but also through landscapes (Philips, 2016). With this said, other aspects of the memorial such as whether the memorial was carved within New Zealand or in Italy cannot be truly confirmed as no source of primary information can be found to confirm either claims. In conclusion, the South African War Memorial was a way for the people to remember the significance that attached New Zealand to the war. In a sense, the memorial can be seen as a cultural memory, where it does not only reflect the past through its symbols but also serves as a remembrance to those who are no longer with us (Dimkovic, 2016). (2475 words)

Bibliography Auckland Libraries. (1873). Auckland Improvement Commission plan of proposed alterations in the City of Aucland. 1873. Retrieved from Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, NZ Map 4475-22. Anon. (between 1899-1902?). Canterbury nurses who served in the South African War. From left to right: Sisters Hiatt, Littlecott, Peter and Webster. Photographer identified. Retrieved from Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22687120. Retrieved from https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22687120?search%5Bpath%5D=photos&search%5Btext%5D=nurses+in+south+african+war Anon. (30 October 1902). THE HON. R. J. SEDDON IN AUCKLAND. New Zealand Herald, p. 1. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19021030.2.80.5?end_date=31-12- 1930&page=3&phrase=0&query=Albert+Park+South+African+War+Memorial&start_date=01-01-1900 Anon. (7 August 1902a). Local and General. Ashburton Guardian, p. 2. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AG19020807.2.11?end_date=31-12- 1930&phrase=0&query=Albert+Park+South+African+War+Memorial&start_date=01-01-1900. Anon. (16 November 1935). MILITARY FUNERAL. Auckland Star, p.10. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19351116.2.80?query=South+Af rican +War+nurses Anon. (22 February 1938). WAR NURSES’ MEDALS. Auckland Star, p. 12. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19380222.2.119.4?page=2&query=South+African+War+nurses Defence Department’s Base Records Branch (1919). Graph of NZEF casualties, 1915 – 1919. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/graph-nzef-casualties- 1915-1919 Dimkovic, D. M. (2016). Memorial Architecture as the Symbol of Remembrance and Memories. South East European Journal of Architecture and Design, 2016(10018), 1 – 6. Gurler, E.E. & Ozer, B. (2012). The Effects of Public Memorials on Social Memory and Urban Identity. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 82(2013), 858 – 863. Inglis, K.S. & Philips, J. (1991). War memorials in Australia and New Zealand: A comparative survey. Australian Historical Studies, 24(96), 179-191. Lambert, D. & The Parks Agency (2015). War Memorial Parks and Gardens: Introductions to Heritage Assets. United Kingdom: Historic England. Heritage New Zealand (2018). South African War Artillery Memorial. Retrieved from http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/556 Paterson, L. (2013). Identity and Discourse: Te Pipiwharauroa and the South African War, 1899 – 1902. South African Historical Journal, 65(3), 444 – 462. Pawson, E. (October 1991). Monuments, Memorials and Cemeteries: Icons in the Landscape. New Zealand Journal of Geography, 92(1), 26 – 27. Philips, J. (2016). To the memory: New Zealand’s war memorials. Nelson, New Zealand: Potton & Burton. William Williams. (circa 1910s – 1920s). The Troopers’ Memorial, Albert Park, Auckland Domain, including statue and canons. Retrieved from National Library, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/30658574 |