AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

An Explanation describes, explains or informs us about an object, situation, event, theory, process, technique or other object of study. Explanations don’t develop an independent argument, so explanations written by different people on the same topic will have similar content, which is generally agreed to be true.

Title: Analysis of the clasped-hand motif

|

Copyright: Anna Chilcott

|

Description: The symbolic meaning of visual images and how this is modified by context: origins and meaning of a gravestone image, and meaning in the context of whom the gravestone commemorated.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

|

Writing features

|

Analysis of the clasped-hand motif

|

The clasped-hands motif can be found on funerary monuments and reliefs from ancient Greece, through the Roman period, and right up until the 18th and 19th centuries when it became increasingly popular with those of the Christian faith. During the Classical Greek period (fourth and fifth century B.C) the clasped-hands motif is thought to have represented the bond between the living and the dead. Elaborate full-body reliefs depicted on funerary stelai were intended not only for the deceased, but for the entire surviving family, with the handshake being a possible symbol of family unity.[1] In early Roman funerary reliefs the handshake depicted between a man and a woman is thought to have represented the union of marriage or, alternatively, the farewell of one partner into the afterlife and the promise of fidelity between the couple after death. In all of these reliefs, as in later gravestone depictions of the handshaking motif, it is the right hand of each individual which is clasped. The right hand represents “the life-force, and is the 'hand of power'.”[2] Traditionally, the hand positioned on the left is known as the 'death hand' while the one on the right is often referred to as the 'life hand'.[3] Dependent on the situation, the handshake could depict a farewell in the event of death, or it could be the greeting of the deceased reunited with loved ones in the afterlife. Alternatively, it could simply be an expression of feeling between family members or married couples.

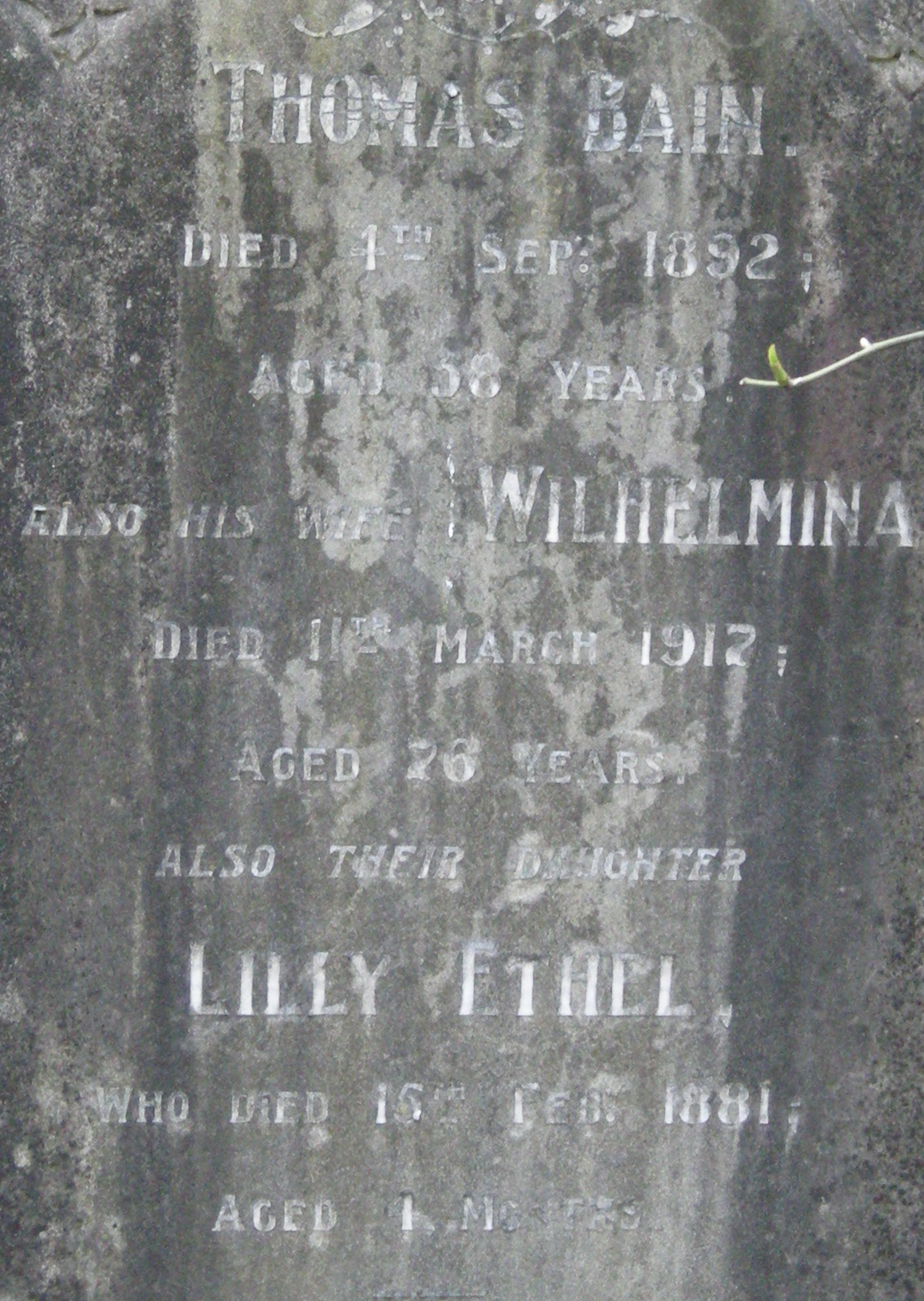

In the context of this gravestone it is possible that the left hand belongs to Wilhelmina, and the right hand is that of her husband, Thomas Bain. Alternatively, the right hand may belong to God himself. The decoration on the left-hand sleeve could imply the deceased is female, and the death of Wilhelmina being the last to occur makes it likely that it is supposed to represent her. However, the date of the tombstone creation is unknown, making it difficult to determine this for certain. The reading of this motif on this particular gravestone would indicate a welcoming into Heaven, while also making reference to holy matrimony. However, the 'life hand' may instead belong to living relatives, and would therefore signify a farewell to both Thomas and Wilhelmina, along with their daughter. To further emphasise all of these meanings, the added Ivy motif below the central symbol is representative not only of immortality and fidelity, but also of attachment and undying affection.[4] Bibliography Davies, Glenys. “The Significance of the Handshake Motif in Classical Funerary Art.” American Journal of Archaeology 89 no.4 (1985): 627 – 640. Foster, Gary S. and Freeland, Lisa N. “Hand in Hand Til Death Doth Part: A Historical Assessment of the Clasped-Hands Motif in Rural Illinois”, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) 100 No.2 (2007): 128 – 146. Gorman, Frederick J. E and DiBlasi, Michael. “Gravestone Iconography and Mortuary Ideology” Ethnohistory, 28, No. 1 (1981): 79 – 98. Keister, Douglas. Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography. Utah: Gibbs Smith, 2004. Lindahl, Carl. “Transition Symbolism on Tombstones“ Western Folklore 45 No.3 (1986): 165 – 185.

[1] Glenys Davies. “The Significance of the Handshake Motif in Classical Funerary Art”, American Journal of Archaeology 89 no.4 (1985): 629. [2] Gary S. Foster and Lisa N. Freeland. “Hand in Hand Til Death Doth Part: A Historical Assessment of the Clasped-Hands Motif in Rural Illinois”, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) 100 No.2 (2007): 130. [3] Ibid: 135 [4] Douglas Keister. Stories in Stone: A Field Guild to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography. (Utah: Gibbs Smith, 2004), 57. |

|