AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

An Evaluation (also called a Critique) evaluates the worth or significance of an object of study (Nesi & Gardner, 2012, p.94). This requires an understanding of the object and a set of criteria by which to evaluate it. Objects evaluated can include books, films, articles, performances, theories, techniques, designs, businesses, products, materials, cultural artefacts etc.

Title: Expressionism in architecture

|

Copyright: Martin Dow

|

Description: Select one principle of 'Modern Architecture' formulated by an architectural historian/theorist including: Kenneth Frampton, Anthony Vidler, Alan Colquhoun, Sigfried Giedion, Reyner Banham, William Curtis or Manfredo Tafuri.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

Expressionism in architecture

|

“Both German Expressionism and Italian Futurism started as movements in the visual arts and literature, though they soon attracted architects dissatisfied both with a moribund Jugendstil and its neoclassical alternative…. [Expressionist architecture] has usually been defined in terms of what it is not (rationalism, functionalism, and so on) rather than what it is.”1

Alan Colquhoun’s definition of expressionist architecture in his book Modern Architecture (2002) leans towards defining the movement in its broadest terms. He notes it steps away from functional and rational styles of architecture, and adopts an artistic abstraction in sync with the development of new art and literature in Germany. The expressionist movement can be accurately linked to a particular setting within the modern architecture movement. Initially started in Germany, the widely recognised time frame of expressionism is from 1910 to 1923.2 In this essay I will discuss the meaning of expressionism and its impact on the modern architecture movement, looking in particular at the Einstein Tower as an example.

German architect Bruno Taut was at the centre of expressionist architecture thus had a big influence on the movement. In an article he wrote in 1914 he suggested there was a “secret architecture” within all artistic works which had the potential to lead to a “wondrous unity” between different aspects of the arts.3 This idea was reiterated by historian Dennis Sharp in 1966 when he wrote “[Architecture] was the great banner under which all the other arts were brought together.”4 A clear theme began within expressionism where architects adopted an avant- garde style of working in relation to abstract art. They were in search of new, irrational forms to communicate expressional freedom as opposed to pure functionalism.

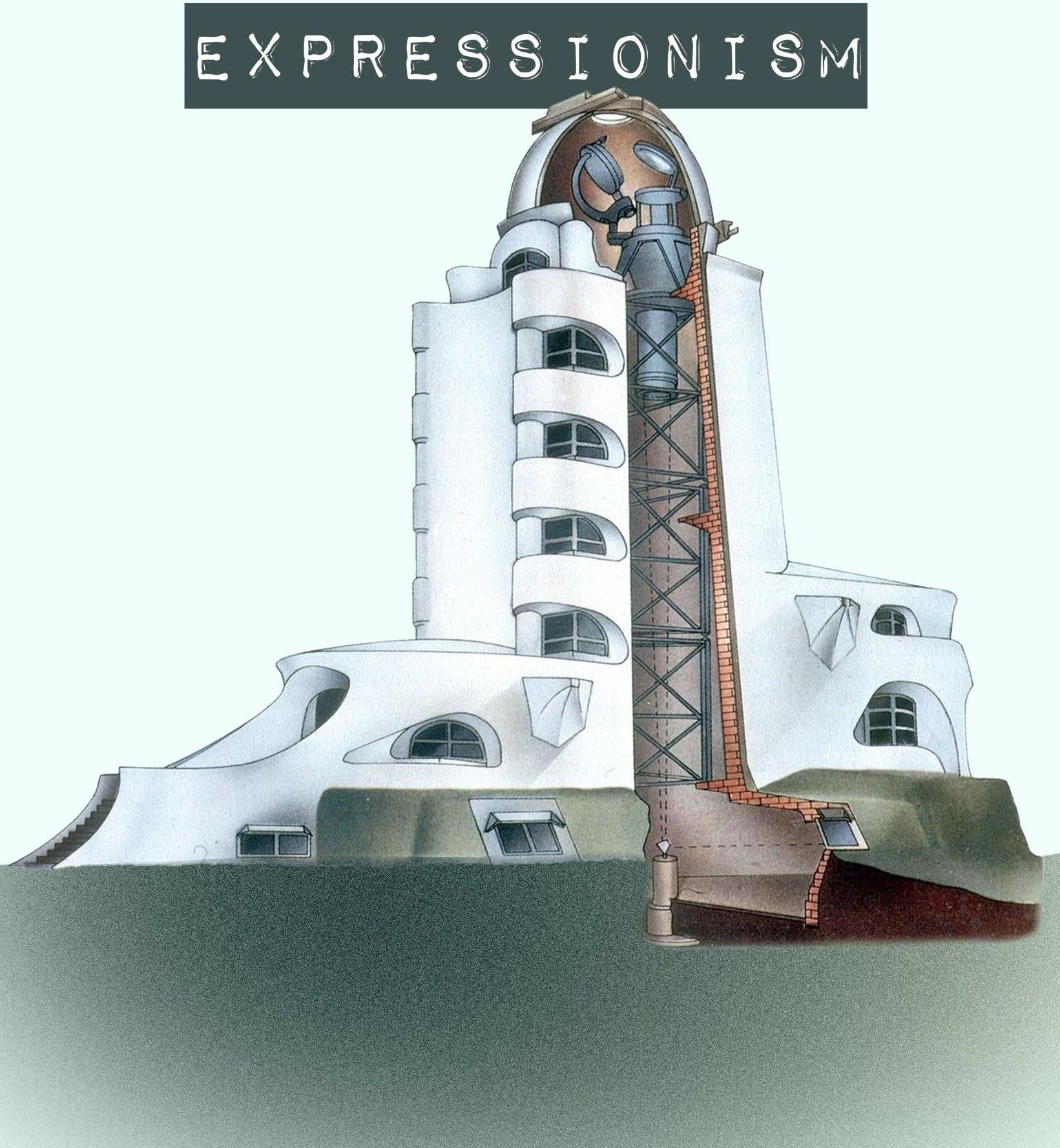

Einstein Tower, Potsdam (1921). Concrete creates a smooth artistic exterior. Gili Merin, “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”, ArchDaily, July 14, 2013, http://www.archdaily.com/402033/ad-classics-the-einstein-tower-erich- mendelsohn

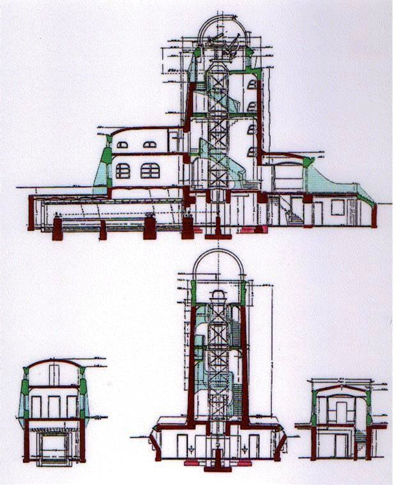

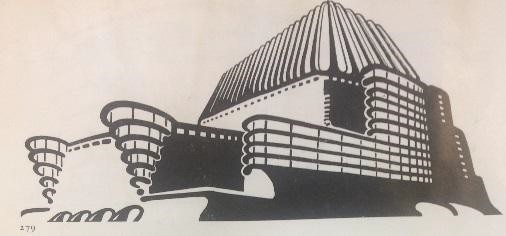

The Einstein Tower built in Potsdam, Germany in 1921 is one of the most famous examples of expressionist architecture.5 Designed by German architect Erich Mendelsohn, the building was first intended to be entirely made with sculpted reinforced concrete, although due to restraints on technology of the time, it was built in brick and covered with a layer of concrete. In this way, it responds to the modern architecture movement by its use of concrete masses, which Mendelsohn constituted as a “true, artistic building material, unlike steel.”6 What makes the Einstein Tower more impressive than other expressionist projects – such as Taut’s Glass Pavilion (1914) – is that, despite its extravagant exterior and reputation, the interior of the building serves its perfect function as an observatory. Elevations and plans for the Einstein Tower – Shows concrete masses (red) and (green). Gili Merin, “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”, ArchDaily, July 14, 2013, http://www.archdai ly.com/402033/ad- classics-the- einstein-tower- erich-mendelsohn

Interestingly, although the period of expressionism had ended by 1923, the Einstein Tower remains a solid symbol of this short lived movement.7 The Tower’s significance has led to architectural historians maintaining that expressionism outlasted its short time frame. Bruno Zevi at the Florence conference on Expressionism in 1964 called it a “permanent feature of modern architecture”,8 and this point was reiterated by Calquhoun where he referred to expressionism as a “permanent and recurrent tendency in modern architecture.”9

Functioning observatory in the centre of the Tower Gili Merin, “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”, ArchDaily, July 14, 2013, http://www.archdaily.com/402 033/ad-classics-the-einstein- tower-erich-mendelsohn There is a great deal of truth to this statement. The Einstein Tower can arguably be called the leading expressionist building; historian Nikolaus Pevsner agrees with this view, arguing that the building “was the first example of a new style of architecture that has since spread all over the world.”1

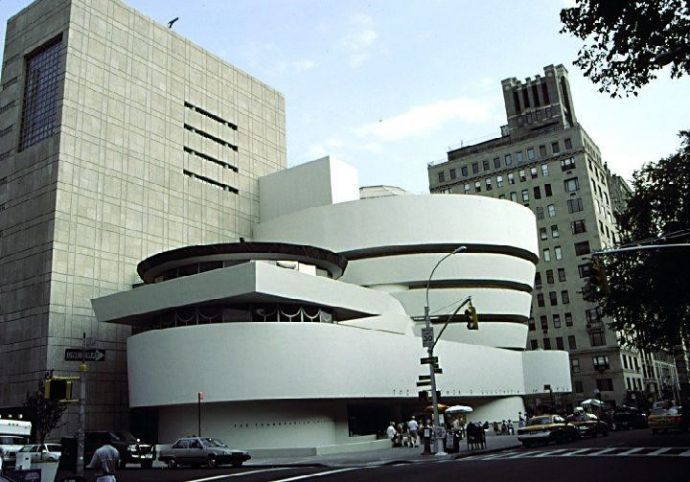

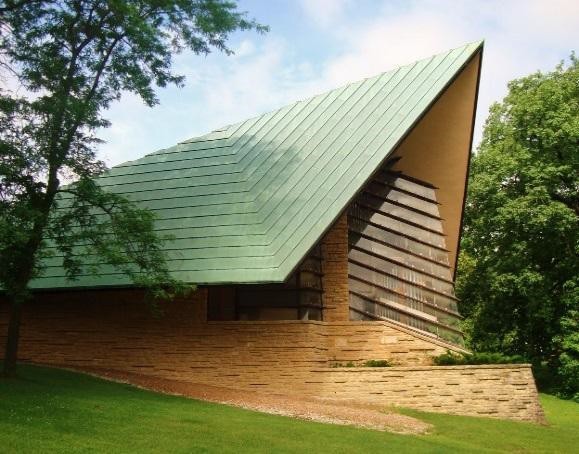

One of Mendelsohn’s biggest influences was on American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In his later years – after World War Two – Wright turned towards a style of expressionism, away from rationalism. A first example of this is shown in his Unitarian Church at Madison (1950), where he adopted a more dramatic style of architecture. The most prolific example of Mendelsohn’s influence on him however, is shown in his Guggenheim Museum (1946-1959) where Mendelsohn comments “his [Wright’s] latest things come close to my first sketches.”11 This comment merely strengthens the view that expressionism can be seen as a permanent feature and not just a short lived movement.

important to note a difference between early stages and post- World War I expressionism. Many of the architects associated with an expressionist style fought in the war, and upon return adopted more radical and emotional designs. This can surprisingly be seen in the first works of Bauhaus (1919) by Walter Gropius; contrasting what the Bauhaus movement was to become.12 It is also worth noting a lot of expressionist architecture remained as paper architecture due to its unrealistic, irrational forms which neither the technology nor economy of the early 20th century could support. While Mendelsohn wanted to build the Einstein Tower in reinforced concrete, rationing due to Germany’s poor economy after WW1 did not allow him to do so. Unitarian Church (1950) – adopting a less rational style Craig, David Cobb. “First Unitarian Meetin House”. Blogspot. Feb 11, 2010. http://davidcobbcraig.blogspot.co.nz/2010/11/wauwatosa-wis.html

This drawback prevented him from building any projects of a similar style, and the Einstein Tower remains his most influential and famous building.

Reasonable opposition has risen against expressionism both during the movement and among historians researching it. During the construction of the Einstein Tower, in a letter Mendelsohn wrote about the project, he pointed out that an official from the State Building Office was entirely “hostile” to his ideas, deeming them an unnecessary “experiment.”13 Since the end of the movement, historians have argued over the legitimacy of expressionism as a feature of modern architecture. Historian Sigfried Gedion in his famous book Space, Time and Architecture (1967) wrote “expressionism [as an art movement] could have no influence on architecture.”14 His view was backed up by reasoning that architecture is an applied art and has too many constraints of materials, construction and economics to be truly expressionist. In some ways his hypothesis is correct (the Einstein Tower for example, was not built how it was first conceived), although architecture is widely recognised to have the capability to embody emotions and stand as an immersive form of tangible art. In that sense Expressionism has endured.

Word Count (not including quote) 1046

1 Alan Colquhoun, Modern Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 87. 2 Dennis Sharp, Modern Architecture and Expressionism (London: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, 1966), 21. 3 Ian Boyd Whyte, David Frisby, (eds.), Metropolis Berlin 1880-1940 (California: University of California Press, 2012), 276. 4 Sharp, Modern Architecture and Expressionism, p.10. 5 Gili Merin, “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”, ArchDaily, July 14, 2013, http://www.archdaily.com/402033/ad-classics-the-einstein-tower-erich-mendelsohn 6 Wolfgang Pehnt, Expressionist Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 121. 7 Gili Merin, “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”, ArchDaily, July 14, 2013, http://www.archdaily.com/402033/ad-classics-the-einstein-tower-erich-mendelsohn 8 Pehnt, Expressionist Architecture, p.11. 9 Alan Colquhoun, Modern Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 89. 10 Oscar Beyer, (ed.), Erich Mendelsohn: letters of an architect (London: Abelard-Schuman Limited, 1967), blurb. 11 Ibid., 18. 12 Oscar Beyer, (ed.), Erich Mendelsohn, 16. 13 Ibid., 53. 14 Cited by Wolfgang Pehnt, Expressionist Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 8.

Bibliography Beyer, Oscar, (ed.). Erich Mendelsohn: letters of an architect. London: Abelard-Schuman Limited, 1967. Craig, David Cobb. “First Unitarian Meeting House”. Blogspot. Feb 11, 2010. http://davidcobbcraig.blogspot.co.nz/2010/11/wauwatosa-wis.html Howe, Jeffery. “A Digital Archive of American Architecture”. Boston College. 1996. http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/fa267/FLW_guggenheim.html Merin, Gili. “AD Classics: The Einstein Tower/Erich Mendelsohn”. ArchDaily. July 14, 2013. http://www.archdaily.com/402033/ad-classics-the-einstein-tower-erich-mendelsohn Pehnt, Wolfgang. Expressionist Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973. Sharp, Dennis. Modern Architecture and Expressionism. London: Longmans, Green and Co Ltd, 1966. Whyte, Ian Boyd, Frisby, David, (eds.). Metropolis Berlin 1880-1940. California: University of California Press, 2012.

|

When studying the ideological setting of the expressionist movement it is

When studying the ideological setting of the expressionist movement it is