AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Likely impact of the Christchurch earthquake on the macro economy of New Zealand

|

Copyright: Finnie Fung

|

Description: The impact of this natural disaster will be discussed by informing the prospect of economic growth in regards to the changes to New Zealand's measured GDP, the effects on economic welfare and cost of living, the interest rate and the financial market, and finally the unemployment rate.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

|

Writing features

|

Likely impact of the Christchurch earthquake on the macro economy of New Zealand

|

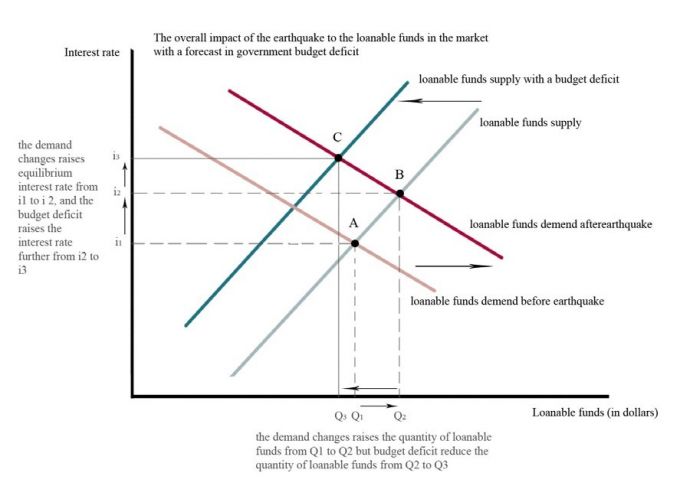

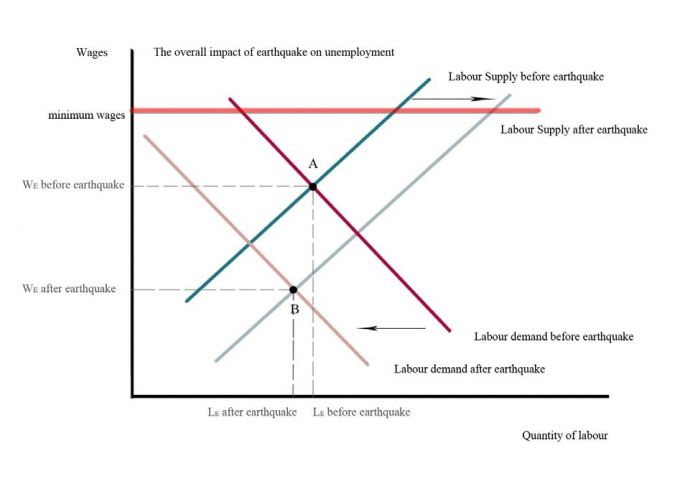

New Zealand's path to economic recovery is going to be long after the impact of the Christchurch earthquake. The deconstruction caused by the September earthquake had already stalled economic growth and production in Canterbury region, and the February earthquake had set the economic growth and recovery back further, affecting the growth in New Zealand’s Gross domestic product (GDP) and the economy, the costs of both earthquakes are estimated to account for about 15% of the New Zealand economic activity (New Zealand Treasury, February 2011). The impact of this natural disaster will be discussed by informing the prospect of economic growth in regards to the changes to New Zealand’s measured GDP, the effects on economic welfare and cost of living, the interest rate and the financial market, and finally the unemployment rate. The preliminary assessment of the impact of the damages to the overall New Zealand economy can be drawn from the measured GDP for the coming years. In late 2010, the growth to the measured GDP had experience a hindered performance as the Canterbury region struggles to pick up the recovery from the last September earthquake. The February earthquake is expected to have a more negative impact on the measured GDP, and the costs amounted to around 8% of New Zealand’s annual output (New Zealand Treasury, March 2011). Nonetheless, reconstruction over the coming years in 2012 will likely offset the negatively and increase the measured GDP to residential, commercial and infrastructure investments (New Zealand Treasury, February 2011). But it is critical for productivity to increase parallel with the rising measured GDP to ensure positive economic growth. Obviously it is no surprise that the measured GDP will be growing as the rebuilding gets underway, but this does not reflect a positive corresponding growth in economic wellbeing and welfare. Economic wellbeing and quality of life is not necessary the output measured in the country’s GDP, and US politician Senator Robert Kennedy had made it apparent in 1968 ‘GDP measures everything, in short, except what makes life worthwhile’ (Mankiw, Bandyopadhyay, & Wooding, 2009). Nevertheless, higher income could be an indication to higher quality of life, or more accurately, high GDP leads to higher quality of life. However, when the measured GDP is growing, the quality of life may not be the same as predate to the earthquake, the widespread catastrophic damages to the entire city and major disruption lies within the memories of individuals, it is a permanence of loss - psychologically and physically. On the other hand, intensive amount of reconstruction will disrupt to an extent the natural resources and environment as a result gives pollution that will be compromise in the future. Additional detriment to the natural resources on top of the earthquake damages will mean that factor of production - natural resources will be reduced, thus reducing the productivity in future growth. Life in New Zealand is already difficult when the recession hit the country; the increased cost of living (measured with the consumers price index, CPI) had already put pressures on households to maintain the same standard of living. The earthquake damages amount to more pressure and stress on households as the reduced outputs by hindered production leads to rising prices on necessities. People simply cannot live without life necessities such as housing, food and transport in the CPI’s basket (Mankiw, Bandyopadhyay, & Wooding, 2009), with a limit budget and the rising price of food and petrol; people would have no option but to cut back cost on other consumption to give the similar standard of living. Nevertheless, problems lie within the CPI measurements of consumptions. Firstly, when prices rise, consumers respond by substituting goods that are relatively less expensive this is most obvious in food consumption. Secondly, an unmeasured quality change may apply to housing; as the building industry suffers the most catastrophic deconstruction, rebuilding is necessary. Except it is likely to predict that the quality of new residential/commercial constructions may not have the same value as predate the earthquake as a consequence of fear and volatility where another aftershock possibly destroy it. Furthermore it is undoubtedly that the quality of Christchurch Cathedral cannot be the same; at least this is what people think. The Government is facing a huge challenge in dealing with the aftermath of the earthquake over the saving, investment and interest rate. Since the earthquake, the financial market runs in chaos as the uncertainty and panic grows, the tentative fluctuations in the financial market discourage people to make savings as they are worry; also discourage investors to invest as they are pessimistic about the future of businesses in Christchurch, or in New Zealand as a whole. The uncertainty and panic increase the risk premium where people decided to hold onto their extra income, which will reduce the supply of loanable funds and the savings the country can generate, that drives the interest rate to go up, leading to problematic issues to the daily operation of the market that will damage financial intermediaries. Increasing interest rate therefore discourages investments because the cost of borrowing increases with the increased interest rate, which reduces profitability. As a result when investors are reluctant and holding back their investments, this will harm the engine of growth in the future by lowering productivity (BusinessDesk & NZ Herald Online, April 2011). When the country does not generate enough savings to fuels the loanable funds supply for investments; the government tries to encourage people to save to mobilise the capital through the channel of donations and other public policies, but this encouragement also makes the financial intermediaries to lift up the interest rate in the market, again this will hold back investments as the cost of borrowing increases. One foremost challenge the government faces is the deficit figures forecast in the budget (NZPA, April 2011). When the government runs a budget deficit, public saving will be negative and this reduces national saving, pushing the interest rate further up and investment will falls, once again reducing the growth rate (Mankiw, Bandyopadhyay, & Wooding, 2009). To stabilise the market, government is reviewing public policies and the monetary policy, in addition to reduce extra funding (Young, March 2011), and maximising the benefit from the export commodity boom which can add a tint of optimism to the limping economy (New Zealand Treasury, February 2011). Furthermore Reserve Bank Governor Alan Bollard lowers the OCR by bringing it down by 50 basis points (NZPA, March 2011). [Illustrated in the graph, in the aftermath of the earthquake, demand for reconstruction is huge that drives an increase to demand of loanable funds, pushing the interest rate up, and the equilibrium moves from A to B. But the budget deficit as a result gives a reduction in national saving pushes the interest rate further up and also reduces the quantity of loanable funds in the market, moving the equilibrium from B to C.] Businesses are more pessimistic about the future after the February earthquake; firms are showing limited expansion in labour inputs as substantial uncertainty remains in the profitability and recovery (New Zealand Treasury, February 2011). These are limiting new investment in labour force (reducing productivity) which may leads to a decrease to the labour demand where equilibrium wages falls. At the same time, many jobs were destroyed forcing an increase to the labour supply, this again pushing the equilibrium wages even lower. Where the demand is low and supply is high, the equilibrium wages is much lower than the minimum wages leading to huge amount of unemployment in a temporary situation.

[Illustrated in the graph below where equilibrium wages falls from A to B (much lower than the minimum wages) in response to the earthquake disruption to the demand and supply]. Accordingly it is critical for the government to mediate and create the additional labour demand to offset the effect of unemployment; this could be done by job creations and leads to support savings as a result. Undoubtedly, the issue is how could government create the additional labour that match each labour their skills and preferences, it is clearly not possible, sectoral shift is a considerable question which amounts to change in the composition of demand among industries. ‘We're about to have the biggest construction project in New Zealand's history’ (NZPA, March 2011). The prospects for the construction and building industry have suddenly changed dramatically as rebuilding is the first priority but the prospects for other industries have drop significantly i.e. the retail and sales service industry, most recently the casino employees – ‘Christchurch will die without it. These are skilled people. They need jobs that match them.’ (Donnell & NZPA, April 2011) This raises numbers of concerns, firstly the young male in the labour force may thrown into the building bloom work-force where it does not match with their skills; secondly the old labour workers will force to be unemployed as there are no demand; thirdly the bloom in the building industry may leads to lower female’s labour-force participation; lastly amongst the different demographic groups, possible increase to unemployment to Maori and Pacific as there are unemployment benefit meaning potential increase to structural unemployment. There will be uncertainty amongst the Asian/other as some are flexible and able to move around the country, but some are not. With a lack of skilled labour, there will be a constraint on rebuilding the city. The labour force is a critical concern because health of human capital has a direct relation to growth and productivity; consequently one simple mistake made now in the labour force could leads to a downturn to the productivity in the future. Overall the outlook in the economic growth is delicate; the economy had experience a hampered performance during the recession, the catastrophic earthquakes that hit the Canterbury region twice just puts the economy into a more fragile and weaker nature. The country once again suffers further loss, disruptions and stagnation in the production that drag down economic growth. Despite the fact that the economic load will be unlikely to share evenly across the country, the February earthquake impact will delay the recovery of the whole country’s economy further for the coming years. The path to economic recovery is going to be long and it seems dark, but we can do it. Word count (including in text citation): 1597 Reference BusinessDesk & NZ Herald Online. (April 2011). Business confidence falls on Christchurch quake, says NZIER. New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 April 2011, from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/economy/news/article.cfm?c_id=34&objectid=10717206 Donnell, H., & NZPA. (April 2011). Casino staff 'thrown on scrap heap'. New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 April 2011, from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/employment/news/article.cfm?c_id=11&objectid=10717006 Mankiw, N. G., Bandyopadhyay, D., & Wooding, P. (2009). Principles of macroeconomics in New Zealand (2nd ed.). South Melbourne, Vic.: Cengage Learning. New Zealand Treasury. (February 2011). Monthly Economic Indicators - February. Retrieved April 1, 2011. from http://www.treasury.govt.nz/economy/mei/feb11/01.htm New Zealand Treasury. (March 2011). Monthly Economic Indicators - March 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011. from http://www.treasury.govt.nz/economy/mei/mar11/03.htm#2 NZPA. (March 2011). Building boom 'will help economy'. New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 1 April 2011, from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10711441 NZPA. (April 2011). Deficit figures point to budget pressures, Key says. New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 April 2011, from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10717073 Young, Audrey. (March 2011). Squeeze on public spending signalled New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 1 April 2011, from http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=10715798 |

|