AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Issues and trends in nursing

|

Copyright: Emma Cavanagh

|

Description: "Over the last sixty years, the image of nursing has changed dramatically depending on the social, economic and political influences of the time period."

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

|

Writing features

|

Issues and trends in nursing

|

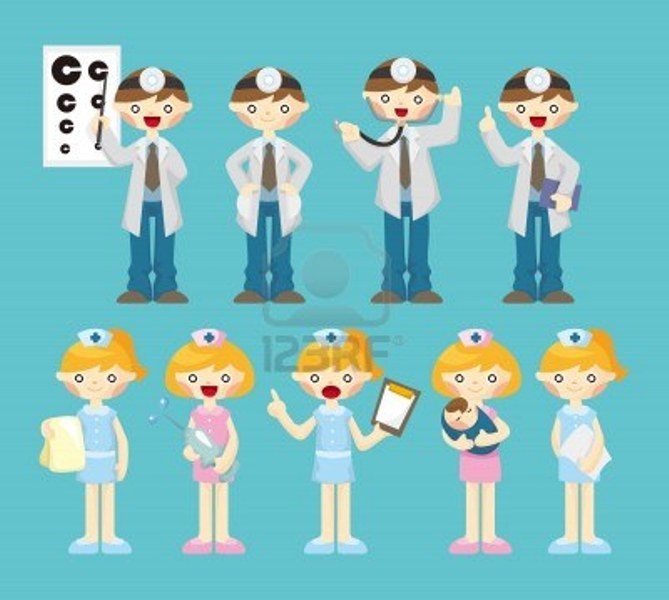

Over the last sixty years, the image of nursing has changed dramatically depending on the social, economic and political influences of the time period. In the past and in many cases, to the present, nursing has been perceived as a feminine profession associated with mothering, a profession subordinate to the medical profession and has been a profession which has been largely sexualised (Elms and Moorehead, 1977). It is important to examine the historical periods, in particular, the ‘Mother’ and the ‘Sex Object’ eras in order to establish where the current public stereotypes have arisen from (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). In addition, it is important to also consider the current issues influencing the image of nursing, such as the media interpretation of the nursing profession. Warner, Black and Parent (1998) argue the traditional stereotypical images of nursing are changing with the rise of regulated nurse education. The image shown is a modern cartoon depicting four doctors, in the top row of the picture and five nurses, in the second row of the picture. The image can be easily found online to purchase as a piece of artwork that can be used in an advertising format (DepositPhotos, 2012). Several apparent features emphasise current nursing stereotypes that have arisen from historical backgrounds. The positioning of the doctors and nurses, as previously mentioned, implies a hierarchy of the medical team as being superior to the nursing team. Furthermore, the physicians are all portrayed as male and the nurses as female, and associated with children. This is a reinforcement of the long standing stereotype that nursing is synonymous with nurturing and mothering and is an inherently feminine profession (Fagin and Diers, 1983). Further to this, the cartoon is placed on a blue background. This could be seen to imply a perceived dominance of males as doctors in the healthcare setting, with blue being a predominantly male colour. Importantly, the nursing staff in the image are all seen to be holding non-technical equipment such as blankets and towels. In contrast, the medical staff are all pictured with stethoscopes and diagnostic tools. This reinforces the commonly held belief that nurses are merely doctors ‘handmaidens’ and their clinical role is purely to assist the physician in what he or she has ordered (Jinks and Bradley, 2003). This aspect of the image also suggests nurses do not have a role to play in the assessment of patients. Finally, the nurses in the image are all pictured in short dresses. This is quite in contrast to the actual role of the nurse in the healthcare setting. This very much depicts the widely held perception of nursing as a sexualised profession. The array of meanings implied in the image are commonly held public views, that have arisen from various historical sources and that still exist today. Two major historical periods, the ‘Mother’ era and the ‘Sex Object’ era, and their associated political and social climates, have largely impacted the public perception of the role and image of the nurse (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). Florence Nightingale contributed to the female image of nursing by consistently defining nurses as female (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). Interestingly, before this period men had received a large amount of nursing education in the West (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). Nightingale nursed through many periods of war and it is possible the social climate of these times meant men were not available for the profession, leading to the first generalisation of nurses as female (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). From this period, it is clear; nursing was, and still largely is, defined as female, as depicted in the image. This perception was perhaps solidified in the post war period of 1946-1965, often called the ‘Mother’ era (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). In the social climate of post-World War Two, women were expected to return to raising children and to be in a subservient position to men (Keddy, Jones Gillis, Jacobs, Burton and Rogers, 1986). The social climate of this era did not support independent career driven women, instead supporting those with materialistic instincts (Fagin and Diers, 1983). These power relations were translated to the work environment where women became to be seen as subservient to the largely male medical profession. It has been suggested this has led to the rise of the stereotype of nurses as doctors’ handmaidens, or in other words, nurses being inferior to doctors and largely female (Jinks and Bradley, 2003). It is clear the nursing profession is often sexualised and this perception is apparent in the picture described. Although this is a widely held view and one which is consistently presented by the media, it is quite contrary to the nurses’ professional role. This stereotype also has historical origins from the mid to late 1900’s (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). However, even before this period, the sexualised image of the nurse was present. Thompson, Shepherd, Plata and Marks-Maran (2011) suggest this image may have arisen as early as the 18th Century where women convicted of prostitution were sentenced to care for the sick, giving rise to the sexual connotations of nursing. Adaryani, Salsali and Mohammad (2012) argue the common white starched uniforms of the 1900’s and the perceived power relationship that can exist between a patient and a nurse led to the role being sexualised. This perception arose from the belief that the nurse had the power to do what they pleased to do to the patient. Darbyshire (2009) also argues the intimate nature of the nurses’ role had a particular stigmatization in parts of the 20th Century. It was perceived that if the nurse was prepared to carry out these actions in their professional life, they would be a willing sexual partner in their private lives (Darbyshire, 2009). Although the sexualised image of the nurse has many historical influences, the perception does still exist and is aided by the media’s interpretation of the nursing role. There are many current factors that also create perceptions like what are shown in the image. To many members of the general public, nurses are still seen as subordinate to doctors. Adaryani, Salsali and Mohammad (2012) argue this may be the fault of the healthcare system itself. It is argued that in the hospital setting, doctors are often referred to using their surname while nurses are referred to by their first name (Adaryani, Salsali and Mohammad, 2012). Adaryani, Salsali and Mohammad (2012) suggest patients may perceive this as a differing level of respect and therefore, a different status level of doctors and nurses. Fagin and Diers (1983) suggest the intimate nature of nurses’ work leads to their role being sexualised in many media sources. A prime example of this sexualisation is discussed by Scott (1999) in relation to a British newspaper talking about ‘busty blonde nurses’. It is important to note doctors do not receive this same type of discrimination and this too, can lead to the public perception of a hierarchy (Scott, 1999). Today, the ideas of the sexualised image of the nurse, of the doctor-nurse hierarchy and of nursing as a feminine profession still exist, as can be seen through the modern cartoon described. Thompson, Shepherd, Plata and Marks-Maran (2011) suggest the lack of clarity of the nursing role in the public eye exists because of ‘nurse invisibility’, in other words in nearly all media portrayals of the healthcare setting, doctors are at the forefront and nurses have small roles to play. Trossman (2003) also discusses the public perception of male nurses as doctors, highlighting the feminisation of nursing does still exist. Although these perceptions are still present, the nursing role is increasingly valued as a worthy career (Warner, Black and Parent, 1998). Elms and Moorehead (1977) suggest the increased reputation of the nursing profession has come about due to the licencing of nurses and due to increased nursing education. Papps (2001) furthers this argument saying nurses are increasingly respected today because of the availability of postgraduate nursing education and because of roles such as the nurse practitioner. Jinks and Bradley (2003) state that in 1994, 4% of people surveyed disagreed that women made better nurses than men, yet in 2002, 53% disagreed. This shows the female image of nursing is slowly changing. From a personal perspective, it could be argued the public perception of the role of the nurse is very different from what is portrayed in the cartoon. People often say the main professional they see while hospitalised is the nurse and recognise the increased level of responsibility the nurse has, technically, in the hospital situation. Although the sexualised image of nursing still exists, few people believe this is the true representation of the profession. It would be fair to say nursing is well respected by the general public and has a significantly different image compared to the last century. As exemplified in the cartoon, nursing has long been seen as a female profession, a profession subordinate to the medical profession and a career which has been sexualised. Many historical events and periods have aided in creating this image and the media continue to perpetuate this view today. Although these perceptions still exist, increased nursing education and licensing is weakening these views. It is clear the image of nursing as a female profession is quickly changing and the sexualisation of the role is becoming less common.

Reference List Darbyshire, P. (2009). Heroines, hookers and harridans: Exploring popular images and representations of nurses and nursing. In J. Daly, S. Speedy & J. Jackson (Eds.), Contexts of nursing: An introduction (3rd ed., pp. 51-64). Chatswood, NSW, Australia: Elsevier Australia. Deposit Photos. (2012). Cartoon doctor and nurse icon. Retrieved from http://depositphotos.com/8307500/stock-illustration-cartoon-doctor-and-nurse-icon.html Fagin, C., & Diers, D. (1983). Nursing as metaphor. The New England Journal of Medicine, 309(2), 116-117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307143090220 Keddy, B., Jones Gillis, M., Jacobs, P., Burton, H., & Rogers, M. (1986). The doctor-nurse relationship: an historical perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 11(2), 745-753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1986.tb03393.x Moorehead, J., & Elms, R. (2007). Will the ‘real’ nurse please stand up. Nursing Forum, 16(2), 112-127. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1977.tb00627.x Papps, E. (2001). (Re)positioning nursing: watching this space. Nursing Praxis in New Zealand, 17(2), 4-12. Rezaei-Adaryani, M., Salsali, M., & Mohammadi, E. (2012). Nursing image: An evolutionary concept analysis. Contemporary Nurse: A Journal For The Australian Nursing Profession, 43(1), 81-89. doi:10.5172/conu.2012.43.1.81 Scott, H. (1999). Nursing professionalism is marred by sexy stereotype. British Journal of Nursing, 8(11), 1. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/docview/199373291?accountid=8424 Thompson, T., Shepherd, J., Plata, R., & Marks-Maran, D. (2011). Diversity, fulfilment and privilege: the image of nursing. Journal Of Nursing Management, 19(5), 683-692. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01268.x Trossman, S. (2003). Caring knows no gender: break the stereotype and boost the number of men in nursing. American Journal of Nursing, 103(5), 65-68. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29745088 Warner, C., Black, V., & Parent, P. (1998). Image of nursing. In G. Deloughery (Ed.), Issues and trends in nursing (3rd ed., pp. 390-441). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Appendix 1

|

|