AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: New Khmer Architecture: A Study of Modernist Cambodian Architecture

|

Copyright: Richard Yi

|

Description: Write an essay on Pacific or South-east Asian architecture built between 1930 to 2008.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

New Khmer Architecture: A Study of Modernist Cambodian Architecture

|

A Study of Modernist Cambodian Architecture and the Buildings Associated with its Creation and Demise

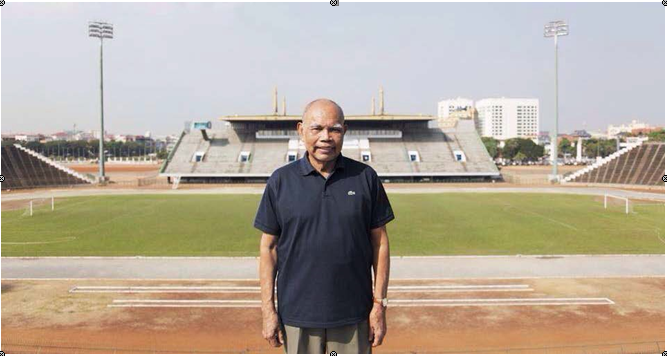

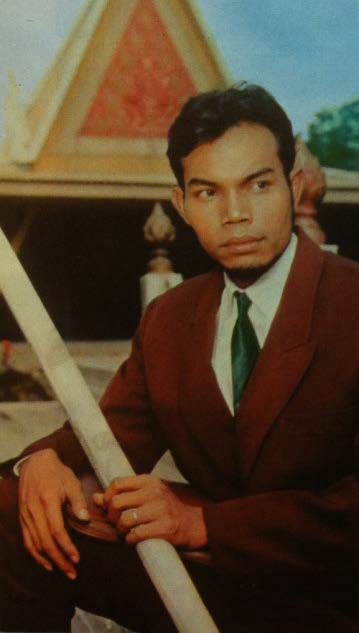

Fig.1 Luke Duggleby, The architect Vann Molyvann standing on the tribune of the National Sports Complex in 2009. 2009. http://www.uncubemagazine.com/sixcms/media.php/1323/Vann_Molyvann57.jpg Cambodia is a country of rich culture and people. One aspect of Cambodian culture has always been revered by both its people and all over the world, that being Khmer Architecture. From Angkor Wat to the Bayon, the architecture of Cambodia links back to its ancient traditions as the late as the 8th century AD. However, the culture of the Khmer people had been suppressed and lost after the collapse of the Khmer Empire and by the rule of a number of foreign nations. Cambodia would finally gain its independence from its colonisers in 1953.1 For a time, a nationalist monarchy known as the ‘Kingdom of Cambodia’ took reign upon the Cambodian peninsula from 1953-1970. During this time, a patriotic influence instigated a new architectural movement in Cambodia known as ‘New Khmer Architecture’2a . This new movement of Cambodian architecture was envisioned and spear-headed by Vann Molyvann, a Cambodian architect that took heavy influences in the artistry, philosophy and aesthetics of vernacular Khmer architecture while introducing modern materials and globalist styles of construction such as modernism and brutalism.2b The Phnom Penh Olympics Stadium and The White Building are both prime examples of how Molyvann’s New Khmer Architecture blends both nationalist and globalist ideas of modern Cambodia in order to create a purely unique style that neither glorifies globalism or extreme nationalism in both a residential and public setting. The New Khmer Architecture movement symbolises the optimistic patriotism and international awareness of Cambodia during this time; a movement birthed from oppressive colonialism and a movement that dies in genocidal nationalism, a movement that signified the second Golden Age of Cambodia.3

Molyvann was an architect; first and foremost. However, he stayed true to his strong patriotic roots as a Cambodian. During his time studying in France, he took a great interest in the “sculptural, structural and humanist” aspects of modern architecture akin to the works of Paul Rudolph and Le Corbusier. His mentor, Gerald Hanning, heavily influenced Molyvann’s direction in architecture as he primarily focused on adapting Khmer architecture in a modern context. Both Hanning and Molyvann would soon work on projects in Cambodia for the

New Khmer Architecture movement. One of their most significant projects for the movement was the Phnom Penh Olympic Stadium (also known as the National Sports Complex). The Phnom Penh Olympic Stadium was commissioned for the 1964 World Games of the New Emerging Forces (an international tournament similar to that of the Olympics) and was to serve as a symbol of Cambodia’s prosperous success as an independent south- east Asian nation to the rest of the world.4 Hanning and Molyvaan tackled this challenge by boldly displaying the philosophies of vernacular Khmer architecture as main features of the building while incorporating modern/global techniques of materiality and structural technology to further exemplify the Khmer influences.

Fig.2 Vann Molyvann Project, Vann Molyvann from Lok Serei. 1953, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5550 c709e4b0e8669eece9f0/t/5583a201e4b075 675dcb4dc2/1434690059687/VM+from+Lok+Serei+%5BFree+World%5D%2C+vol+7+no+ 5%2C+1958.jpg?format=500w Fig.3 Stadium Data Base, Phnom Penh National Olympic Stadium 5. 2011, http://stadiumdb.com/pictures/stadiums/cam/phnom_penh_national_olympic_stadium/phnom_p enh_national_olympic_stadium05.jpg

The stadium’s square plans that are orientated on the cardinal axis harkened back to the layout of many Angkor temples where construction heavily relied on rigid composition rules.5 This rigid plan worked well with the engineering of Vladimir Bodiansk’s construction work on the use of natural reinforced concrete and supports on the stadium. The classical Khmer use of water was also on bold display in the centre of the stadium that followed a similar idea to motes, dykes and canals used in classical Khmer architecture and planning. This was especially important due to Cambodia’s identity as an amphibian nation where water symbolised purity, food and transportation. The building opened in November 12, 1964 with high praise, having 100,000 people attending the inauguration ceremony. Many saw this moment as a symbol of Cambodia’s strong significance in the world and had boosted an already strong patriotic spirit within the country.6 Many consider this era as the Second Golden Age of Cambodia. Today, the Phnom Penh Olympics Stadium is considered to be one of the most well-preserved, strongly-utilised and revered buildings to come from the New Khmer Architecture movement. In a recent poll, an overwhelming 97% of local Cambodians shared the opinion of preserving the building during a massive reconstruction plan of Phnom Penh.7 This massive support for the Phnom Penh Olympic Stadium could be attributed due to Molyvann’s design to make the building a proud and clear symbol for Cambodian culture and artistry while keeping the building internationally appealing with structural and material influences from current global trends.8 The building was designed in a way to powerfully display Cambodian patriotism with a strong awareness of global architecture. "In my architecture there are no hidden structures. Everything is visible9," Molyvann said about the building.

Fig.5 Sa Sa Art Projects, The White Building soon after completion. 1965, https://cambodiaandbeyond.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/screen-shot-2014- 07-22-at-10-32-42-pm.png

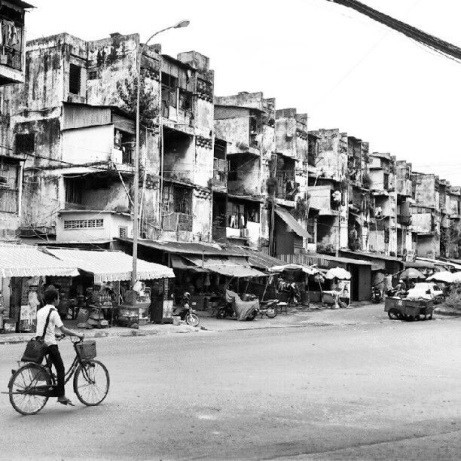

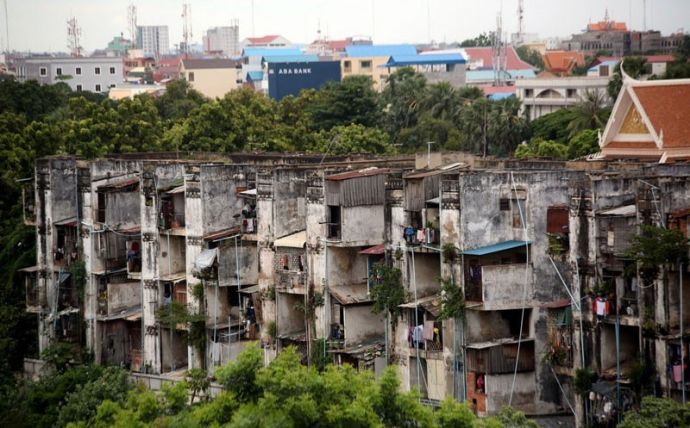

successful. The White Building was Molyvann’s attempt at created a rigid apartment complex in Phnom Penh that followed many of the ideas of his other works such as the Phnom Penh Olympics Stadium. It was a key building of the Cambodian riverfront social housing plan in 1963.10 Although Molyvann had worked on residential complexes and houses before, this project turned out to be much larger in scale. The building was designed to be well-suited around the customs and habits of the Khmer living tradition while integrating modern trends in materiality and structural machinery. The plan of each suite follows a similar layout of many traditional Khmer wooden houses where main spaces are allocated to sleeping and living areas while kitchen and bathroom areas are designed to be secondary space. These two hierarchical spaces are separated to prevent odour from passing through. The building also implements locally produced materials such as clay bricks in certain parts of the buildings to induce a sense of familiarity for the residents while keeping true to some parts of Khmer construction.11 However, the White Building also features modernist features such as using materials like rigid reinforced concrete as a main structural skeleton for the apartment while having opened areas at the back of the building that allows for natural ventilation and sunlight throughout the apartment.12 The residents of the building appreciated the familiarity that the traditional layout brought while enjoying the convenience and security that came from the modern features. The White Building always held a tradition of hosting artistic talents from all across Cambodia whom have enjoyed the flexibility and familiarity of the building. However, after a bloody seven-year civil-war, the New Khmer Architecture movement would soon be halted under the Khmer Rouge in 1975. Fig.6 Marianne Waller, The White Building. 2012, https://cambodiaandbeyond.files.wordpress.com/2014 /07/screen-shot-2014-07-22-at-10-32-42-pm.png

The Khmer Rouge was an ultra-nationalist government that suppressed individual expression that did not meet its values and had committed genocide towards the minorities and “deviants” whom many were artist. The White Building was almost destroyed during this period with many of its residents either fleeing or murdered during the Cambodian Genocide. 13 The Khmer Rouge collapsed in 1979, but the damage was done. The residents who survived moved back into the White Building, but the decades that followed had diminished Cambodia’s once strong integrity. With a crippled economy, an unstable political system and a number of natural disasters, Cambodia was in turmoil.14 The damage done to the White Building could not be fixed and maintenance could not be provided. In July 2017, eviction notices were given to residents of the White Building. A few months later, it was demolished for a new residential plan for Phnom Penh that threatens to destroy most of the buildings built during New Khmer Architecture movement, including many of Molyvan’s works.15 The White Building and many others like it signify the life and death of the Second Golden Age.

Fig.9 The Cambodia Daily, Historic White Building to Be Demolished. 2014, https://www.cambodiadaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/cam-photo-white-building2.jpg

From Angkor to the Barons, Khmer architecture has always been a strong aspect of pride and identity for Cambodia. However, these traditions have been suppressed or forgotten due to the rise of colonialism from other nations (such as France and Japan). Colonial-rule had dictated the arts, lifestyle and architecture for Cambodia until in 1953, Cambodia finally gained independence. 16 Many consider the years that followed (1953-1970) to be the Second Golden Age of Cambodia. The nation’s economy boomed, patriotism strengthened and the arts were wholly unique. Vann Molyvann’s and his work in New Khmer Architecture signifies this time of prosperity and global relevance. His buildings focused on displaying and inhabiting the traditional philosophies and systems of Khmer architecture while introducing modern use of materiality and building techniques. This combination of both global and vernacular architecture had generated revered iconic buildings that are appreciated by both Cambodians and internationally.17 The use of global trends were always utilised to further develop and signify the traditional features of the buildings. However, this era of affluence came to an end under the rule of the Khmer Rouge. This was when the most dangerous form of nationalism took control of Cambodia, leaving a trail of destruction of all things considered to be impure of Cambodian tradition. Some of New Khmer buildings survived, but others were either completely destroyed or damaged beyond repair. This period in Cambodia’s history taught the world the dangers of both an extreme form of suppressive globalism and the destructive nature of pure nationalism. This was the period when New Khmer Architecture thrived, and the period when it would eventually die. Word Count: 1602

Bibliography Baumgärtel, Tilman. Sthapatyakam: The Architecture of Cambodia. Phnom Penh: Royal University of Phnom Penh, 2010. Doyle, Shelby. “City of Water: Architecture, Urbanism and the Floods of Phnom Penh.” Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning, no.6 (2010): 135-154. Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. Havana, Omar. “The last days of Phnom Penh's iconic White Building.” British Broadcasting Service. Updated July 24, 2017. 40T 32TUhttps://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-40652014U32T Im, Chanboracheat. Can Phnom Penh’s Olympic Stadium Withstand the Force of Globalization? Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2016. Louth, Jonathon. Saving the White Building: Storytelling and the Production of Space. Adelaide: Flinders University, 2012. Nam, Sylvia. “Phnom Penh: From the Politics of ruin to the Possibilities of return.” T.S.D.R., no.1 (2011): 55-68 Sereypagna, Pen. “White Building: Smart City.” Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning, no.11 (2015): 101-110. Simone, AbdouMaliq. “The politics of the possible: Making urban life in Phnom Penh.” Tropical Geography Vol.20, no.2 (2008): 187-204. Teulings, Jurriaan. “Pick up Where It left off in the 1960s, Cambodia is in Throes of Change as it Catapults itself into the 21P century.” Khmer Chameleon, vol.72 (2017): 75-80. Yimsut, Ronnie. Facing the Khmer Rouge: A Cambodian Journey. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Footnotes: 1 Yimsut, Ronnie. Facing the Khmer Rouge: A Cambodian Journey. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011. 2a Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. 2b Fujiki, Meril Dobrin. Cambodian Modern: Vann Molyvann and the New Khmer Architecture. Honolulu: East-West Seminars Program, 2016. 3 Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. 4 Bodach, Susanne. “New Khmer Architecture: Iconic vernacular buildings under threat?” Pacific Geographies, no.48 (2017): 11-13. 5 Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. 6 ibid 7 Im, Chanboracheat. Can Phnom Penh’s Olympic Stadium Withstand the Force of Globalization? Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2016. 8 Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. 9 ibid 10 ibid 11 Sereypagna, Pen. “White Building: Smart City”. Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning, no.11 (2015): 101-110. 12 Sereypagna, Pen. “White Building: Smart City.” Nakhara: Journal of Environmental Design and Planning, no.11 (2015): 101-110. 13 Louth, Jonathon. Saving the White Building: Storytelling and the Production of Space. Adelaide: Flinders University, 2012. 14 ibid 15 ibid 16 Yimsut, Ronnie. Facing the Khmer Rouge: A Cambodian Journey. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011. 17 Grant Ross, Helen & Collins, Darryl Leon. Building Cambodia: "New Khmer Architecture" 1953-1970. Bangkok: The Key Publisher, 2006. |

Not all of Molyvann’s New Khmer buildings turned out to be as revered or as

Not all of Molyvann’s New Khmer buildings turned out to be as revered or as