AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Reconstruction of Knossos

|

Copyright: Nicholas Redman

|

Description: A research essay about a particular topic covered in the course, in this case the ancient Greek site of Knossos, with specific emphasis on its controversial reconstruction.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

Reconstruction of Knossos

|

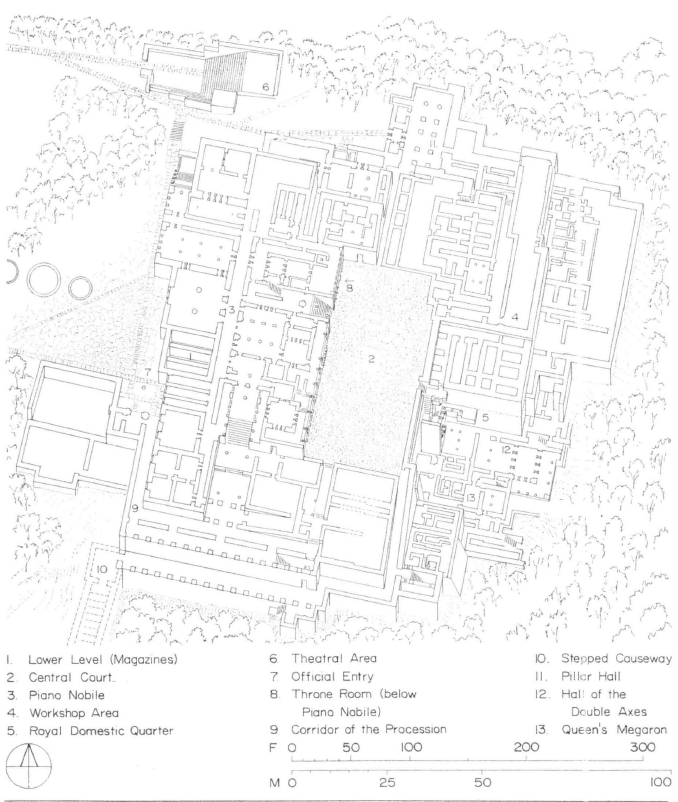

The idea of reconstructing architecture has always has been subject to conflicting views within the architectural community. Architectural history is now better informed with new advances in the field of archaeology, so it can be expected the revaluation of ancient sites will become more prolific as time goes on. In this essay the ideas of ancient excavation and reconstruction specifically in Greece will be examined, concentrating on the ancient site of Knossos and its reconstruction by Sir Arthur Evans. A critical analysis of Evans’ process of excavation and reconstruction will be undertaken and then compared with the sites historical context, an analysis of the man Sir Arthur Evans, as well as where it sits in the wider scheme of ancient architecture and its relationship with modernity. Knossos; a city located in ancient Crete: supposed Capital to King Minos the Creator of the Minoan civilisation.[1] The site is located 8 kilometres inland from Crete’s North coast and is set to be the stage for a highly civilised Bronze Age culture.[2] It has been claimed as Europe’s oldest civilisation.[3] Figure 1 – Map of Knossos ruins in axonometric plan Businessman Archaeology The discovery of Knossos is considered to be one of three crucial architectural discoveries of the early twentieth century, the other two being the discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb and also the abnormally abandoned site of Ur in Mesopotamia.[4] That being said its reconstruction has claimed to have been “a monument to one mans (Evans) conception of that civilisation” making it possibly unprincipled in its reconstruction.[5] For it was Evans’ claims of its mythical qualities within site particularly with his “Labyrinth” discovery and its relation to the Greek myth of Theseus, Ariadne and the slaying of the Minotaur deep under the ‘Labyrinth’ (Knossos) is what particularly turned the heads of scholars, philosophers and tourists alike.[6] But what is to be understood is the social and economic landscape of these discoveries, particularly in Greece at the time. A man that is crucial to understanding the nature of these discoveries and these reconstructions is Heinrich Schliemann.[7] Schliemann was the creator of ‘businessman archaeology’ one where popular appeal and either misrepresenting or exaggerating discoveries was undertaken in a bid for further monetary gain.[8] After Schliemann’s successes at Troy and Mycenae the race to find other Greek legend sites was on.[9] This kind of archaeology needs to be fundamentally understood when unpacking the discoveries of Knossos and its followed reconstructions.

Changes in Knossos Knossos was a constantly developing state and had seen many changes in culture, architecture and its urban fabric. The site has seen 9000 years of interaction, in 4000 of these years civilisations have in turn appeared and disappeared.[10] The Bronze Age of Crete spanned from c.2000-1100BCE.[11] Its reconstitution was a mixture of different time periods that make up the Palace.[12] Upon excavation and the beginning of reconstruction there were some changes made to the site that have been criticized. Firstly in terms of materiality; Knossos was known for its use of mineral gypsum, found at local quarries around the site it is reputable for its distinctive reflective light qualities.[13] During reconstruction extensive use of concrete was used, both as fillers and as pure form, which has been deeply criticized.[14] Cathy Gere, a lecturer in the History of Science at the University of Chicago claimed in regards to Evans use of concrete in the restorations: “Parts of Knossos were pure modernism: the throne room complex comprises three stories of unadorned square concrete pillars…like a flimsy Le Corbusier exercise.”[15] Initially wood and brick was used, followed by double-T steel bars, then post World War 1 reinforced concrete was implemented.[16] This use of concrete was seen as a ‘spirit of the times’ move, Evans was the first person to use reinforced concrete in Greece for such a job.[17] Joseph MacGillivary, writer of ‘Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth’ comments in regard to reinforced concrete: “it was the basis for Le Corbusier’s New Architecture… It was a time of reconstruction…Architects wanted to build a new world (post WW1)… reinforced concrete gave modern architects the ability to create a new world for their living population, so it gave Evans exactly the same ability to create a new world for ancients.”[18]

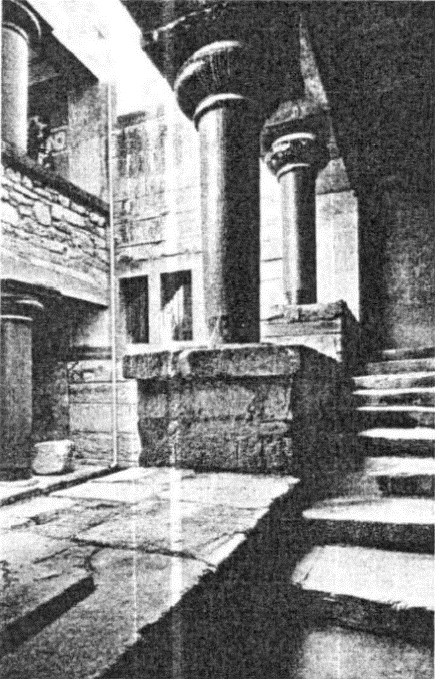

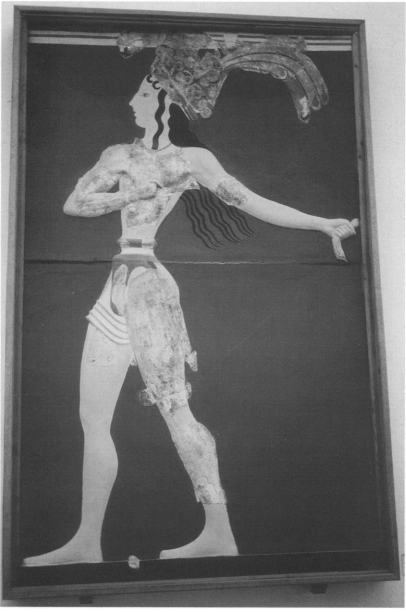

The change of Knossos in terms of its architectural layout have also been questioned: Evans believed the ‘Piano Nobile’ (main floor of Palace) was accessed by a ‘monumental stairway’ all located in the ‘South Propylaeum.’[19] Saying this there is little evidence to prove that this ‘monumental stairway ever existed.[20]Additionally, in the reconstruction Evans implied another staircase connecting the ‘Piano Nobile’ to a third floor, but again there is no evidence of this being the case.[21] To conclude some of these many changes is potentially important in terms of today’s understanding of Knossos as a Greek Mythical site and is in regard to the many Frescos discovered. One of the most influential frescos supposedly reconstructed was the Fresco depicting the ‘Priest King’ has been proven to actually be remade from a number of different frescos discovered by Evans’s team in other parts of the site.[22]

The supposed fabrication of the “Priest King” fresco has influenced the perception of the whole of the Knossos myth. Many stories regarding an overall ruler of the Minoan civilisation exist, despite the fact that even to this day there is no evidence that there was ever an overall ruler at any Minoan site.[23]There is little evidence to reinforce the claim that the Minoan people were ever ruled by a monarchy, save for the fabricated reconstruction of iconography collaged from Evans’ salvaged fragments of other frescos on site, rendering the argument practically obsolescent.[24] Saying this there is evidence that the Minoan people were exposed to monarchy due to their sea-faring ventures so ruler iconography can be assumed.[25] Possibly it is from Egyptian contact that this iconography was generated, as the headwear worn by the “Priest King” can be paralleled with headwear only seen on Egyptian Sphinxes and priestesses within Minoan culture.[26] Figure 2 – Reconstructed “Monumental stairway”

Figure 3 – Reconstructed “Priest King” fresco The Sir Arthur Evans Palace From these changes the question presents itself: Why did Evans make these changes? Were they intentional? A current hypothesis to his perception of Knossos when excavating can be read through the writings of German academic’s; Hans Robert Jauss’ theory on reception.[27] It is proposed that nothing can be seen as “absolutely new in an information vacuum,” and anything discovered can only be perceived from ones past experiences and learnings.[28] When analysing Evans’ work it can be seen he was a wealthy Englishman with a higher education in the Victorian era, paired with his meeting of Schliemann may be the reason for Evans thinking he had found a ‘Palace’ as opposed to possibly a township.[29] It may be the possible that his perceived discovery is really a result of the social political state of affairs of England at the time along with his education planting ideas of Monarchy and Eastern priest Kings into his perception of the discovery.[30]Evans may have unconsciously searched for ruler iconography and manipulated the excavation and reconstruction to fit the narrative he was wanting to discover.

Knossos and Modernity Although these changes may to some be considered relatively subtle, its effect on modernity could be considered relatively substantial. With the discovery of Knossos the influence on writing and art due to a perception shift in classical Hellenism brought many writers and tourists in flocks with recent air travel development to the mythical site. In particular with reference to two philosophers; Sigmund Freud and Oswald Spengler we can see the influences. Sigmund Freud was interested in prehistoric Aegean archaeology and also was a collector and antiquities of Mycenaean and Cypriot origin.[31] Freud was known to have had Evans’ books, and the way Evans’ writings helped formed Freud’s writing on psychoanalysis can be described as: “(psychoanalyst, unlike archaeologists) can sooner or later see their objects whole and clear, and hold them fast.”[32] Similarly the writings from Evans on Knossos were also used by Oswald Spengler in his writing of “Decline of the West.”[33]

Also its influence on art and literature cannot be ignored. The evidence of wider cultural landscape in Greece other than the solely perceived Classical Greece that Virginia Woolf experienced, made her question whether the idea of one Classical Greece was nothing but an illusion.[34] Books such as ‘The Bull from the Sea’ (1942) and ‘The Kind Must Die (1958) both by Mary Renault, by her account were written around the time she visited and wandered Knossos.[35]

In terms of architecture the influences of direct form appear minimal. This being said Evans reconstruction showed a clear bridging between the classical form and the modern form. For Evans, Knossos was the origin of the classical.[36]The Classical style of architecture was seen in architecture at the time for example in the works of Adolf Loos. Loos saw classical architecture as the ultimate form, the pure forms of classical can been have seen to have been undertaken by Loos.[37] In projects such as Michaelerhaus (1909-11) in Vienna he claims the classic elements were in no way ornamental but essential to structure just like the structure of Knossos and other Classical sites.[38] From here it can be deduced that the architecture of Loos was one that strived to be classical but be void of the ornamental; a stylistic architectural origin that both Loos and Evans independently saw in Knossos.[39]

With all these influences and connections of Modernity to Knossos but also the seen fabrications and changes constructed by Evans, one must ponder if Knossos would have been such an influential site for the world if such changes were not undertaken and a neutral unbiased view was taken with the discovery, excavation, and reconstruction of Knossos.

Figure 5 – Michaelerhaus, Adolf Loos, in classical style

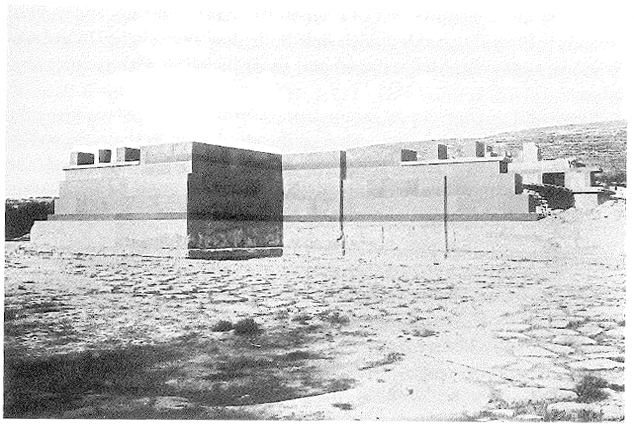

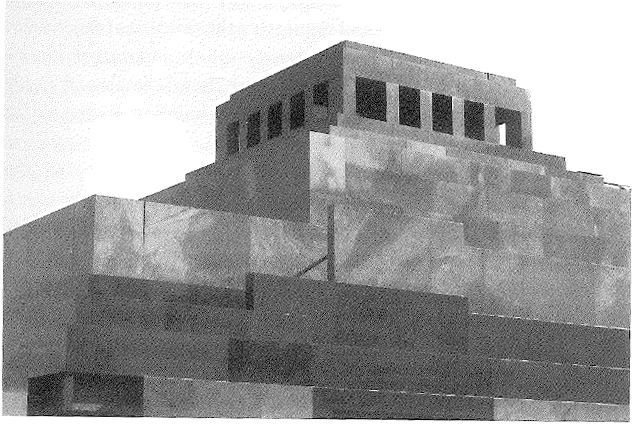

Figure 5 – on the left: the west reconstructed façade of Knossos taken in 1930. On the right: the Lenin Mausoleum, Moscow built 1930. As can be seen there are extreme similarities between the ancient site and the modern building.

As has been seen, the discovery and reconstruction of Knossos cannot be considered a pure, unbiased representation of Minoan culture. But like all history as the time between Evans reconstruction and today becomes longer, the reconstruction too one day will become also part of its own history and lineage of the site. Although the reconstruction of Knossos has been heavily criticized by archaeologists, architects and historians for the last one hundred years, perhaps instead of the current consensus of the site being seen as damaged or corrupted by these reconstructions it can be seen as a perusal of the site consistent with the education and upbringings of one man in the Victorian Era. Rebecca Dickson, writer of “The Evansian Period of Knossos: Inconvenient History and the World Heritage List’, claims the period of 1900-1930 to be an “Evansian Period” in the history lineage of Knossos.[40] This may be a more appropriate way to approach Knossos; understanding the time periods and constant changes that have gone through the site over history and seeing Evans’ interaction as just one of those period of interaction that has brought the historical site as it sits today. A perspective worth considering can be seen in the controversial quote: “History is written by the victors.” - Winston Churchill, in the modern world the victor could be considered the one of power and paired with our capitalist world, one with the most wealth. Although a saying with many counter arguments, there is an argument here of the one with the most wealth is the one who has written history. Word count: 2170 (including footnotes) Bibliography Cadogan, Gerald. “ “The Minoan distance”: the impact of Knossos upon the twentieth century.” British School at Athens Studies 12, (2004): 537-545. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40960812. Dickson, Rebecca. “The Evansian Period of Knossos: Inconvenient History and the World Heritage List.” Fabrications 26, no.1 (2016): 102-120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2016.1131134. Davis, Ellen N., ed. Paul Rehak “Art and Politics in the Aegean: The missing Ruler,” in “the role of the ruler in the prehistoric Aegean”, Aegaeum 11, (1995): 11-12 Douglas, Carl. “Architecture and the Archaeological Excess: Sir Arthur Evans’ Reconstruction at Knossos.” MArch(Prof) Thesis, University of Auckland, 2004. Duke, Philip G. The Tourists Gaze, The Cretans Glance: Archaeology and Tourism on a Greek Island, Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2007. Evans, Sir Arthur. Scripta minoa: the written documents of Minoan Crete with special reference to the archives of Knossos, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909. Gere, Cathy. Knossos and the prophets of Modernism, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009. Grammatikakis, Giannis., Konstantinos D. Demadis, Kristalia Melessanaki, and Paraskevi Pouli. “Laser-assisted removal of dark cement crusts from mineral gypsum (selenite) architectural elements of peripheral monuments at Knossos.” Studies in Conservation 60, (2015): 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1179/0039363015Z/000000000201. Harrington, Spencer P.M. “Saving Knossos.” Archaeology 52, no.1 (1999):30-40. https://www.jstor.org/stabe/41771476. Hitchcock, Louise A. “Minoan Architecture : A contextural Analysis.” American Journal of Archaeology 106, no. 1 (2002). https://doi.org/10.2307/507203. Hood, Sinclair, R. D. G Evely, Helen Hughes-Brock, and Nicoletta Momigliano. Knossos: A Labyrinth of history: Papers in honour of Sinclair Hood, Athens: British School at Athens, 1994. Karetsou, Alexandra. “Knossos after Evans: past interventions, present state and future solutions.” British School at Athens Studies 12, (2004):547-555. https://ww.jstor.org./stable/40960813. Kostof, Spiro. A history of architecture: Settings and rituals, Oxford: Oxford University press, 1995. McEnroe, John C. Architecture of Minoan Crete: Construction identity in the Aegean Bronze Age, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010. Palmer, Leonard R. On the Knossos Tablets, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963. Shaw, M.C. “NEW LIGHT ON THE LABYRINTH FRESCO FROM THE PALACE AT KNOSSOS.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 107, (2012): 143- 159. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068245412000032. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Knossos.” Published February 26th 2016. https://www.britannica.com/place/Knossos. UNESCO. ”Minoan Palatial Centres (Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Zakros, Kydonia).” published on Janurary 16th, 2014. http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5860/. ”Minoan Palatial Centres (Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Zakros, Kydonia),” UNESCO, accessed on September 27th, 2018, http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5860/. Figures: Figure 1 - Kostof, Spiro. A history of architecture: Settings and rituals, Oxford: Oxford University press, 1995, 110 (fig. 5.25). Figure 2 - Kostof, Spiro. A history of architecture: Settings and rituals, Oxford: Oxford University press, 1995, 112 (fig. 5.28). Figure 3 - Shaw C. W. “The Priest King”, courtesy Archaeological Museum of Herakleion, Herakleion Figure 4 – Bouchard, Karen. “Goldman & Salatsch Building View Description: exterior, front” 1910, Brown University. In Artstor accessed September 27, 2018. http://library.artstor.org.eproxy2.lib.hku.hk/#/asset/ASAHARAIG_1112113542 Figure 5 - Gere, Cathy. Knossos and the prophets of Modernism, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009, 3.

[1] ”Minoan Palatial Centres (Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Zakros, Kydonia),” UNESCO, accessed on September 27th, 2018, http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5860/. [2] Ibid. [3] Gerald Cadogan, “ “The Minoan distance’: the impact of Knossos upon the twentieth century,” British School at Athens Studies 12, (2004): 541. [4] Ibid., 537. [5] Alexandra Karetsou, “Knossos after Evans: past interventions, present state and future solutions,” British School at Athens Studies 12, (2004): 547. [6] M.C. Shaw, “NEW LIGHT ON THE LABYRINTH FRESCO FROM THE PALACE AT KNOSSOS,” The annual of the British School at Athens 107 [7] Cathy Gere, Knossos and the prophets of Modernism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009), 17. [8] Ibid. [9] Ibid. [10] Rebecca Dickson, “The Evansian Period of Knossos: Inconvenient History and the World Heritage List,” Fabrications 26, (2016): 105. [11] Ibid., 105. [12] Karetsou, “Knossos after Evans”, 547. [13] Giannis Grammatikakis, Konstantinos D. Demadis, Kristalia Melessanaki, and Paraskevi Pouli, “Laser-assited removal of dark cement crusts from mineral gypsum (selenite) architectural elements of peripheral monuments at Knossos,” Studies in Conservation 60, (2015): 3. [14] Ibid. [15] Gere, Knossos and the prophets of modernism, 1. [16] Spencer P.M. Harrington, “Saving Knossos,” Archaeology 52, (1999): 35. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid. [19] McEnroe, John C. Architecture of Minoan Crete: Construction identity in the Aegean Bronze Age, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 73. [20]Ibid. [21]Louise A. Hitchcock “Minoan Architecture : A contextural Analysis.” American Journal of Archaeology 106, (2002): 30. [22] Dickson, “The Evansian Period”, 106. [23] Ibid., 107. [24] Ibid. [25] Ellen N. Davis, “Art and Politics in the Aegean: The missing Ruler,” in the role of the ruler in the prehistoric Aegean, Aegaeum 11, (1995): 11-12. [26] Hitchcock, “Minoan Architecture,” 80-81. [27] Dickson, “The Evansian Period”, 109. [28] Ibid. [29] Ibid. [30] Davis, “Art and politics”, 12. [31] Cadogan, “The Minoan distance,” 539. [32] Ibid. [33] Ibid. [34] Ibid., 540. [35] Ibid., 543. [36] Carl Douglas “Architecture and the Archaeological Excess: Sir Arthur Evans Reconstruction at Knossos,” (MArch(Prof) thesis, University of Auckland, 2004), 78.) [37] Ibid. [38] Ibid., 79. [39] Ibid. [40] Dickson, “The Evansian Period”, 104. |