AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Campaign to reduce drinking during pregnancy

|

Copyright: Delia Cotoros

|

Description: How to design a NZ-specific campaign to reduce drinking during pregnancy.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

|

Writing features

|

Campaign to reduce drinking during pregnancy

|

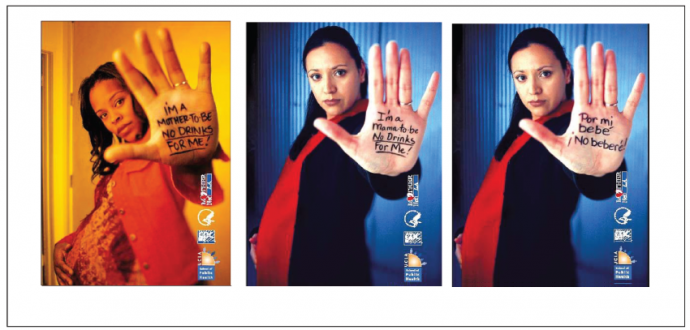

Statistics show that drinking during pregnancy and the effects of this are a real problem in many countries. Despite this, there is no social marketing campaign in place in New Zealand aimed at changing this behaviour. Social marketing campaigns developed in other countries can offer useful information and can be used as a template for developing a campaign for New Zealand, however, it must be acknowledged that New Zealand is unique and therefore a New Zealand specific campaign must be designed accordingly in order to be effective. Social marketing uses commercial marketing tools, principles and techniques to promote voluntary behaviour that improves the health of a target population (Kotler & Zaltman, 1971). Social marketing is different from commercial marketing because it promotes concepts, services and products that aim to change behaviour for the gain of the people, while in commercial marketing, a service or product is being marketed for financial gain (Kanekar & Sharma, 2007). Social marketing is a well-planned, long term process that may involve cessation of certain behaviours (e.g. drink driving), changing some behaviours (e.g. drinking water instead of soft-drinks) or doing something new (e.g. using sun block). Because the ultimate goal is to achieve behaviour change, it is crucial to understand people’s motivations, needs and beliefs about the behaviour but also understand the context in which the behaviour takes place (the effects of commercial marketing, societal norms, peers, community, legal and economic context, etc) (Bridges & Farland, 2003). There have been many social marketing campaigns in New Zealand in the past few years, on a broad range of issues such as eating fruits and vegetables (5+ A Day), exercising (PushPlay) and getting mammograms, to more addictive behaviours such as smoking and gambling (Ashfield-Watt, 2006; BreastScreen Aotearoa, 2004; Ministry of Health, 2004; Schofield, 2003; Woodward, 2003). Some of the most prevalent social marketing campaigns have focused on drinking alcohol. The campaigns have ranged from television ads, printed media, radio and magazine ads, and focused on topics such as drink driving, binge drinking and the effects of being drunk (e.g. violence). However, one important aspect of drinking alcohol has not been featured in any marketing campaign in New Zealand: drinking while pregnant. Alcohol is a teratogen, therefore drinking during pregnancy can cause developmental disorders and deformities in the unborn baby. Regular heavy use and binge drinking, especially early in the pregnancy can lead to Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) (AHW, 2006). FASD is characterized by mental retardation (low IQ, poor attention, language disabilities), other neurological disorders (seizures, hypersensitivity to sound, hyperirritability), craniofacial malformations, low birth weight, kidney, heart and skeletal defects, etc (Stratton et al., 1996). The risk of being born with FASD and the severity of the condition increases with the amount of alcohol consumed during pregnancy (Day, et al, 2004). Specialists have not found a type or amount of alcohol that is safe to be consumed during pregnancy (even one glass of wine can impair the development of the central nervous system of the baby), therefore the current WHO recommendation is to avoid any alcohol during pregnancy (AHW, 2006). Overseas research estimates that FASD affects 1 in 100 live births (Gossage & May, 2001). The number of people with FASD is unknown in New Zealand, but studies have shown that there could be thousands of children at risk of FASD, based on the number of mothers that are drinking while pregnant. A national New Zealand study in 1994 showed that 41.6% of women drank alcohol while pregnant (Counsell, et al, 1994). A report in 1999 showed that 29% of pregnant women continued to drink after it was confirmed that they were pregnant; more than this, 11% of them regularly drank until they were intoxicated throughout their pregnancy (AHW, 2006). A study in 2002 found that 25% of pregnant women at 6 months admitted to having drunk alcohol in the previous week (McLeod, et al, 2002). All these studies in New Zealand show a real problem regarding drinking during pregnancy, yet no social marketing campaign has been implemented to attempt to change this behaviour (AHW, 2007). However, other countries have developed campaigns aimed at drinking during pregnancy and the potential for FASD. In 2003, Glik and colleagues (2008) introduced in two areas in Southern California a social marketing campaign that was developed with the input of the community. Formative research had shown that the two chosen areas (Compton and Bakersfield) had communities with low educational and income levels, and multiple ethnic groups (the main ethnic groups were Caucasian, African-American and Latino). Six focus group interviews were conducted in order to assess women’s knowledge about the potential harm of drinking while pregnant. The participants in the focus groups suggested that the target audience should be women aged 18 to 35 as they believed younger women drank more and that commercial alcohol advertising targets younger women. The focus groups also revealed that the participants had received conflicting messages from friends, family and even health care providers: they heard from several sources that they should not drink while pregnant, but they also heard or been told that certain types of alcohol or drinking at certain times during the pregnancy is safe. For example, some women felt that because wine and beer are not as strong, they wouldn’t have the same effects as spirits and liquor therefore making them safe to consume. The goal of the campaign was to encourage women to abstain from drinking alcohol during pregnancy (Glik, et al, 2008). It was decided to promote the campaign through posters, take-one cards, and T-shirts. The posters were placed in areas where women of childbearing age go (beauty salons, convenience stores, clothing stores, restaurants, etc). The T-shirts and take-one cards (which were smaller versions of the posters with information on the back regarding the potential harms of drinking while pregnant) accompanied the posters in schools, clinics and community organisations. Many participants in the focus groups wanted to use realistic pictures of babies with FASD in order to shock people but it was decided to use images of women who were concerned about their babies’ health and therefore decided not to drink. Different pictures and slogans were pretested with the focus group participants. Two slogans were selected by the participants: “Missed your period? Don’t drink period” (Appendix A) was used in Bakersfield and “I’m a mama-to-be, no drinks for me” (Appendix B) was used in Compton, with translations in Spanish in order to appeal to the Latino population. The first slogan was chosen to address the fact that many women are not sure if they are pregnant or not, and they continue to drink (Glik, et al, 2008). Surveys were carried out to evaluate the impact and exposure of the campaign. The participants in the surveys were women 18 to 35 years old, residing in the areas where the campaign took place. The results showed that the exposure rate of the survey respondents to the campaign materials was 54.2% in Compton and only 11.2% in Bakersfield. There were no differences in exposure associated with pregnancy status, age or ethnicity. Although the outcome was below the desired level (the exposure rates are small), the campaign did offer some beneficial information that can be used in future campaigns. For example, the formative research revealed that women receive conflicting messages regarding drinking during pregnancy. This is very important to keep in mind when creating new campaigns so that this can be countered. The difference in exposure rates between the two areas may be due to the way the materials were distributed. In Compton, which is smaller geographically, more campaign materials were distributed in fewer places while in Bakersfield the materials were spread out (many venues had only one poster). As a result, the exposure rate in Compton is higher, perhaps due to the materials clustered together which would draw more attention. Another reason for the difference in exposure rates may be due to the visual aspect of the campaign materials. It may be that the items used in Compton were more memorable than the ones used in Bakersfield as result of images, colours and messages used. The images used for the posters in Bakersfield are in light colours, placed upon a light blue background. In contrast, the images used in Compton had bright blue, orange and red, making the posters stand out. The models in the Compton posters are also pregnant, which is more relevant to the campaign’s message, compared to the headshots of the models in the Bakersfield posters. More than this, the models in the Compton posters also look more determined, and the outreached hand toward the viewer is more likely to grab attention. Another point to note is that the slogan used in Compton “I’m a mama-to-be, no drinks for me” promotes motherhood, determination and empowerment, giving a sense of pride in refusing drinks, making the poster more appealing to the audience. On the other hand, the message used in Bakersfield, “Missed your period? Don’t drink period” denotes a sense of guilt for falling pregnant (Glik, et al, 2008). As mentioned before, the percentage of women drinking during pregnancy indicates a significant problem in New Zealand, therefore a social marketing campaign should be developed. The campaign done by Glik and her colleagues in the United States could serve as a template for a New Zealand version. As there has never been such a social marketing campaign in New Zealand, it would be useful to do formative research before the campaign is developed, in order to assess New Zealand women’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviours regarding drinking while pregnant. Using the community’s input to design and implement the campaign like Glik did may also be useful, as it may increase the likelihood of appealing to community members. To begin with, the campaign should be introduced only in a certain area, as it will make it easier to evaluate its effectiveness. It might be useful to choose an area that has a diverse population so that the evaluation can reveal if variables such as ethnicity, income, education levels and culture influence the outcomes. The target population of women aged 18 to 35 identified by Glik could be a good starting point for New Zealand, however formative research and focus group interviews might suggest extending the age range from 15 or 16 to 40, given the high rate of teenage pregnancies and women having children late (Cribb, 2009; Fergusson, et al, 2001). The main objective of the campaign is to prevent FASD by promoting abstinence from alcohol during pregnancy. Along this, another goal is to counter the mixed messages the women are receiving regarding drinking during pregnancy: a survey of health professionals in New Zealand showed that less than 50% of the practitioners surveyed advised women not to drink while pregnant, therefore mixed messages may also be a problem in New Zealand (Leversha & Mark 1995). The campaign can start off similar to the one developed by Glik: using posters, fliers and take-one cards. Following Glik’s example, the printed media can be placed in beauty stores, clothing stores, pharmacies, health clinics, etc. In addition, billboards could also be used. The low exposure rates in Glik’s campaign suggest that the message did not reach its target audience as intended. Therefore, using billboard advertisements as well as other printed media is more likely to capture audience attention: people are more likely to pay attention if they have seen the images and posters in other places and if they look familiar (Glik, et al, 2008). Participants in Glik’s focus groups initially suggested using strong graphic images of babies with FASD in order to shock people. However, research has shown that fear messages do not always work: for example, it has been found that people with lower education levels or with lower social economic status are less responsive to shock messages (Hastings, et al, 2004). Many of the drink-driving campaigns use shock ads and graphic images, and a high use of shock ads can lead to people getting tired and ‘tuning out’ from the message. Therefore, shock images shouldn’t be used in a New Zealand campaign, especially since it can offend people with FASD. Instead, images similar to the ones used in the Compton posters should be used: determined women, taking control of their lives and taking care of their babies. Based on the observations made on Glik’s campaign, it might be more useful for the posters to use clear images in strong, bright colours (like the Compton posters), rather than softer and lighter coloured images (like the Bakersfield posters). A number of different slogans should be pre-tested with focus groups, but messages similar to “I’m a mama-to-be, no drinks for me” are a good starting point. As mentioned before, women receive mixed information about drinking during pregnancy. One way to address this issue is to incorporate a specific side message into the campaign. For example, including a phrase such as “No beer, no wine, no alcohol, NO WAY” in the poster can make women realized that no type of alcohol is safe. The main message would still be a positive “I’m a mama to be...” slogan, and the “No beer, no wine, no alcohol, NO WAY” text can be in smaller writing at the bottom of the poster. Glik used different posters to appear to Caucasian, African-American and Latino women. New Zealand is a very multicultural country, with many different ethnicities, therefore it would be hard to make different posters for each. Caucasian, Maori, Asian and Pacific islanders are the most prevalent ethnicities, and although it is easy to make posters with models of each of the four ethnicities, doing the posters in different languages may be a challenge, as there can be several languages for similar ethnicities (e.g. Asian ethnicity includes Chinese, Korean, Jappanese, etc) (Goodyear, 2009). The formative research and focus group interviews should reveal community opinions on which should be included. An important aspect of social marketing campaigns is that they are not public education campaigns: social marketing is focused on changing behaviour while education campaigns are focused on raising awareness and improving knowledge (Bridges, & Farland, 2003). In order for the marketing campaign to be more effective, it is recommended for an education campaign to run in parallel. As mentioned above, women are aware they shouldn’t drink while pregnant, but they have heard conflicting messages or are not aware of the potential harms and how FASD manifests itself. Therefore, an education campaign would ensure women have the adequate information, while the social marketing campaign encourages them to abstain from drinking, making it more likely for the campaign to be effective. Statistics indicate that drinking during pregnancy is a real problem in New Zealand, and perhaps is time to develop a social marketing campaign in order to change this behaviour. Developing a campaign that is specific to New Zealand will be a challenge as there are many different things that must be taken into account, such as different ethnicities, different languages, appropriate messages and slogans and dealing with mixed messages that women receive. Campaigns introduced in different countries can serve as a template or a starting point, but formative research would be an appropriate and useful first step in developing a New Zealand specific campaign against drinking during pregnancy.

References

AHW. (2006). Alcohol Health Watch: Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: The effect of alcohol on early development. Fact Sheet. Retrived on 10th of October, 2009 from http://www.ahw.co.nz/FASD_FactSheet26.7.06.pdf. AHW. (2007). Alcohol Health Watch: Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in New Zealand: Activating the Awareness and Intervention Continuum. Briefing Paper. Alcohol Healthwatch Action on Liquor, 2007. Retrieved on 10th of October, 2009 from http://www.ahw.co.nz/pdf/FASD_paper_20.4.07.pdf. Ashfield-Watt, P. (2006). Fruits and vegetables, 5+ a day: are we getting the message across? Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 15 (2): 245-25. BreastScreen Aotearoa. (2004). More about breast screening and BreastScreen Aotearoa. Ministry of Health, Learning Media Limited, Wellington, Retreived on 9th of October, 2009 from http://www.nsu.govt.nz/Files/BSA/BSA_Booklet.pdf Bridges, T. & Farland, N. (2003). Social Marketing: Behaviour change marketing in New Zealand. Special edition: Social marketing conference. Wellington, October 2003. Retreived 9th of October, 2009 from http://www.senatecommunications.co.nz/files/Updated_soc_marketing.pdf Counsel A, Smale P and Geddes D. (1994) Alcohol Consumption by New Zealand Women during pregnancy. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 107 (982): 278-281. Cribb, J. (2009). Focus on families: New Zealand families of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 35. Day, N., Leech, S. & Willford, J. (2004). Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and cognitive status of children at age 10. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30(6), 1051-1059. Fergusson, D., Horwood, L. & Woodward, L. (2001). Teenage pregnancy: Cause for concern. New Zealand Medical Journal, 114(1135): 301-303. Glik, D., Eilers, K., Myerson, A. & Prelip, M. (2008). Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Prevention Using Community-Based Narrowcasting Campaigns. Health Promotion Practice. 9: 93-103. Goodyear, R. (2009). The differences within, diversity in age structure between and within ethnic groups. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand. Gossage, P. & May, P. (2001) Estimating the Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: A summary. Alcohol Research and Health. 25(3): 159-167. Hastings, G., Stead, M. & Webb, J. (2004) ‘Fear Appeals in Social Marketing: Strategic and Ethical Reasons for Concern, Psychology and Marketing, 21 (11): 961-86. Kanekar, A. & Sharma, M (2007). Social marketing for reduction in alcohol use. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 51(4), 3-6. Kotler, P. & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social Marketing: an approach to planned behaviour change, Journal of Marketing, 35, 3-13. Leversha, A. & Marks, R. (1995). Alcohol and pregnancy: Doctors’ attitudes, knowledge and clinical practice. New Zealand Medical Journal, 108, 428-300. Mcleod, D., Pullon, S., Cookson, T. & Cornford, E. (2002) Factors influencing alcohol consumption during pregnancy and after giving birth. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 115(1157). Ministry of Health. (2004). Preventing and Minimising Gambling Harm: Consultation Document: Summary of Submissions. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Schofield, G. (2003). Push Play: what’s under the umbrella? New Zealand Medical Journal, 116 (1179): 534-536. Stratton, K., Howe, C. & Frederick, B., (1996) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention and Treatment. Institute of Medicine Division of Biobehavioural Sciences and Mental Disorders, National Academy Press. Woodward, A. (2003). What do we need to do to reduce smoking among teenagers? New Zealand Medical Journal, 116(1180): 558-560.

Appendix A.

Bakersfield posters: Caucasian, African American, and Latina (Spanish) Posters (Glik, et al, 2008) Appendix B:

Compton posters: African American, Latina (English), and Latina (Spanish) Posters (Glik, et al, 2008) |

|