Fig. 1. The interior of the central space in Hagia Sophia showing the application of pendentives. (Photograph by Tahsin Aydogmus, in Kleinbauer,” Hagia Sophia,” 82.)

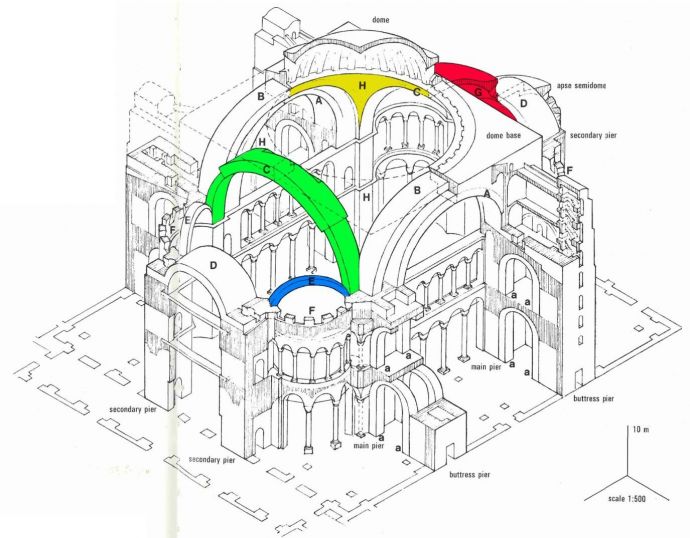

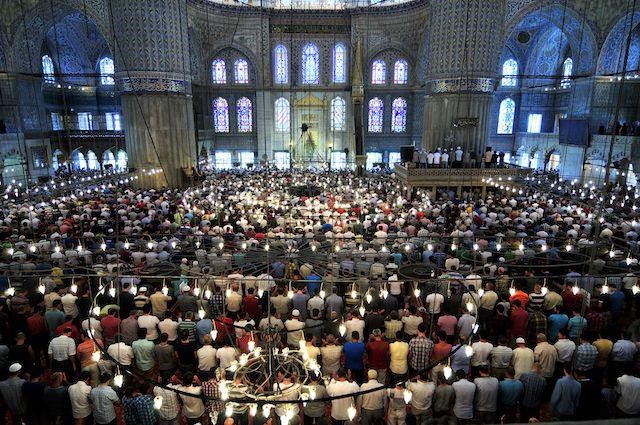

The construction of domed buildings unequivocally existed before Hagia Sophia, which was born in 537 CE during the Byzantine era under the rule of Emperor Justinian. The dome and semidome structure were probably ancient Roman invention and had been used routinely in public bath houses. Hitherto the most famous dome building before Justinian’s was the Pantheon in Rome, built some four hundred years earlier, in the 2nd century AD.1 The dome of the Pantheon was the largest dome ever built in its era, but this came with a trade- off. The superstructure of the dome was designed by the archetypal method of earlier dome buildings which rested directly on circular walls. This technique limited and determined both the shape and size of the building, but the architects of Hagia Sophia, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles had designed a more avant-garde structural system, that allowed for an interior that is much larger and not limited by the size and shape of the dome. This was achieved by placing the 31m sized dome on the square base of four immense arches that rested on four prodigious piers, and not on the exterior walls like the Pantheon. The transition from the square base to the round dome was attained by filling in gap corner spaces with spherical triangles called pendentives.2 This structural innovation made it possible to expand the building with vaults and semidomes far beyond the extent of the Dome.

Fig. 2. The structural system of Hagia Sophia. Main semidome (red), pendentive (yellow), main arch (green) and smaller semidome (blue). (Drawing by Rowland Mainstone, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 73.)

However, the original dome of Hagia Sophia only lasted just over two decades and collapsed in May 558 after a series of earthquakes.3 The nephew of Isidore of Miletus, Isidore the Younger had been put in charge of rebuilding the dome.4 It is interesting to look back at the time before and after the edifice was completed and also the changes after the reconstruction. What triggered the architect’s imagination to design such brilliant structural system for the uniquely harmonious cluster of dome and semidomes superstructure, and the lessons we can gain from the collapse and after the reconstruction which influenced later constructions?

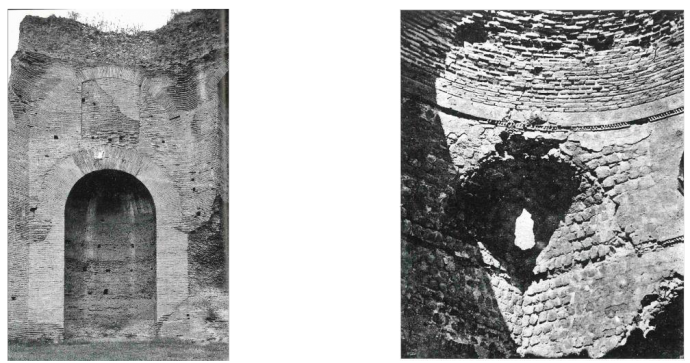

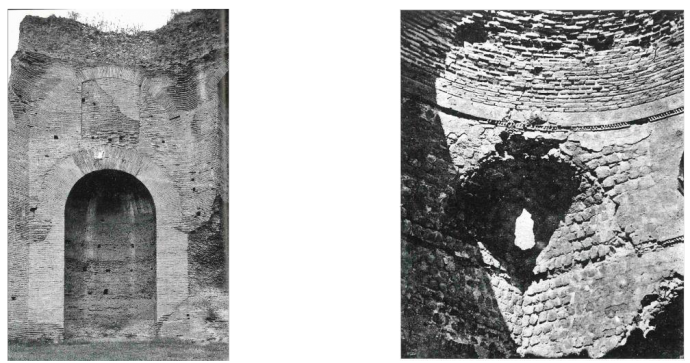

In accordance with the aforementioned structural system, the four brick pendentives which bounded the dome to the square base of four thick semicircular arches of bricks was a really brilliant structural innovation and played an important role for the existence of Hagia Sophia. 5 Eventhough there was no exact prototype of this unprecedent scale pendentive that rose to a height of 41.5 metres before the construction of Hagia Sophia, the possible structural precedents which resemble ‘pendentive-like’ structure had been seen in earlier buildings. It was presumably developed from an earlier construction technique of placing the dome over polygonal rooms of the Baths of Caracalla. The dome and the octagonal wall was bounded by bridging the corners with fuzzy structures to fill the gap resembling pendentives. The technique was occasionally used to bridge the corner of the square room, but on a much smaller scale.6

Fig. 3. (left) Pendentive-like structure in the Baths of Caracalla. Fig. 4. (right) Squinch that filled the gap corner in the Sausanian palace of Firuzabad. (Photographs by Josaphine Powell, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 163.)

The next possible structural precedent for pendentive is the technique of arching the course of the brick in the corners, known as the squinch. This construction technique can be seen in the Sausanian palace of Firuzabad.7 The arch across the corner was a separate element to fill the upper gap of the meeting point and the corner must be bridged like a pendentive- like form. However, like the former technique, the scale of the project is still rather modest compared to Hagia Sophia to become the answer for its structural problem, but they possibly acted as the starting point for Isidore and Anthemius in creating the pendentive.8

Apart from the pendentive, the use of adjoining semidomes as a solution to extend the dome which then created a uniquely harmonious expanse of interior and exterior form was brilliant. The semidomes did not only expand the central dome space, the nave and created a balanced composition uninterrupted by the supporting structure on the floor level, but it also served as the buttresses to the dome superstructure along the east-west axis of the monument.9 As mentioned before, the semidome was probably a Roman innovation. It was used over apsidal recesses in basilicas, public baths and apses of churches. Based on the detailed observation of the structure, the characteristics of semidome with free standing forward edge as its crown has the tendency to move forward. This forward movement of the crown between 1/30th and 1/50th of the span was considered common for the masonry semidome in particular.10 If the semidome butts were placed against another object or surface, the thrust load can be pass from the crown to it, reacting the same way as the arched flyers of flying buttress.11 Thus, if known, revealed the feasibility of semidome to serve as buttress if it is built against something else forming the interplay of hemispherical elements in the cluster of dome superstructure like in Hagia Sophia.

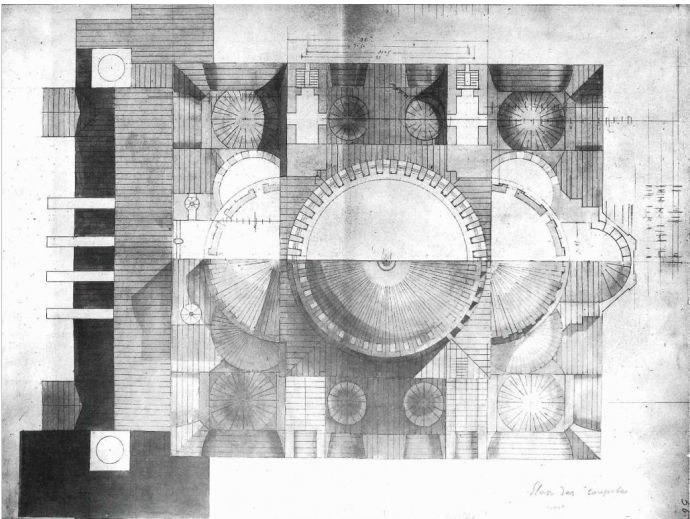

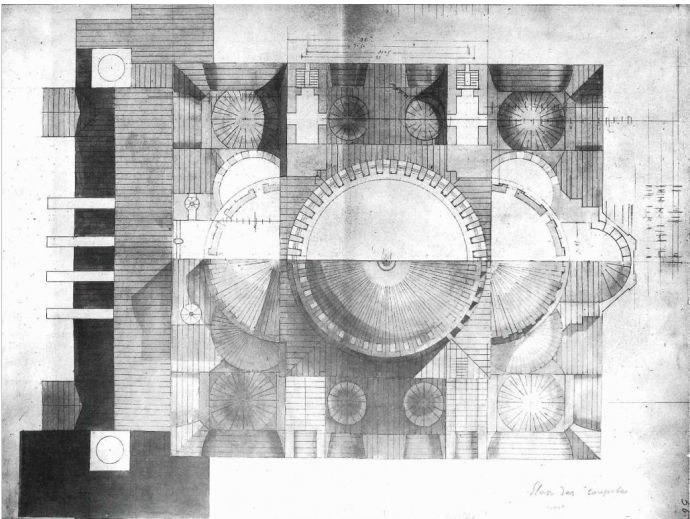

Fig. 5. Plan of the multiple dome roof. (Drawing by Charles Texier, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 24.)

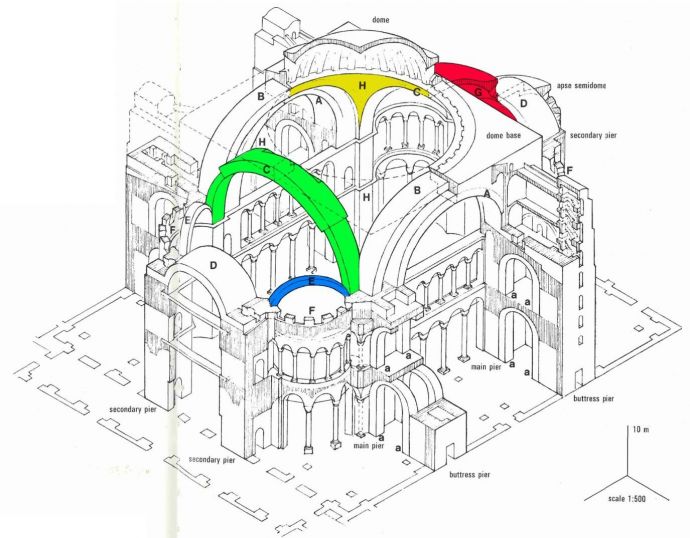

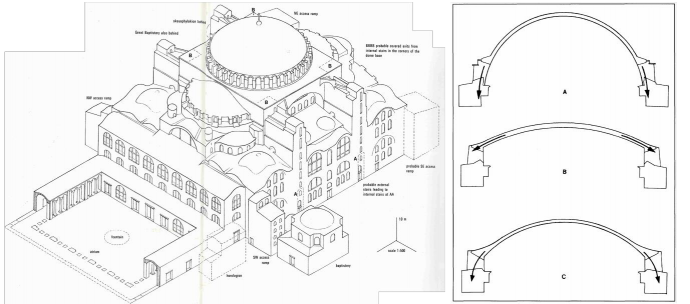

The first dome fell along with the eastern main arch and the eastern half dome. As there were a lot of lesson gained during the design and construction process, the collapse of the edifice does not give any less or probably even more lessons to us. It has been generally accepted that the seismic force from the earthquakes indeed severely injured the building, but it was also due to the faults in the initial design. The deformation was partly from the feebleness of the piers and buttresses to hold disruptive forces from the lateral thrust of the dome.

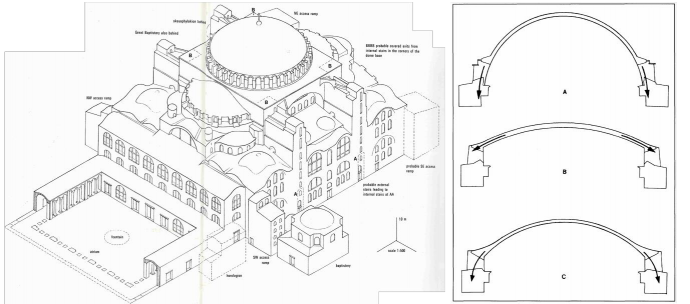

The excessive lateral thrust of the dome was evoked from the original dome’s low curvature. Although the precise form of the original dome of Anthemius and Isidore of Miletus was just merely presumptions from the sparse textual records, Procopius described that the original dome is 20 feet lower than the second dome which is the present dome that stands today. This statement was also supported by Malala’s claim and if it is accurate, the original design of the dome must be extremely shallow compared to the present dome, possibly the curvature of the dome was aligned with the pendentive This was a faux pas in dome construction because as the shallower the dome, the greater lateral thrust generated from it.12

Fig. 6. (left) Reconstruction of the exterior as in 562. Fig. 7. (right) Thrust line diagram for dome profiles. The top dome is the present dome (A), the middle is the platter dome (B) and the bottom is the approximate profile of original dome. (Drawing by Rowland Mainstone, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 121.)

During the reconstruction of the second dome, Isidore the Younger had attempted to solve the structural problem by demolishing the original dome entirely. He cut down the excessive lateral thrust by increasing the curvature to an almost hemisphere-like shape to remedy the flaw of original design. It has been recorded that the unknown configuration of the first dome gave a greater impact to amaze eyewitnesses than its substitute.

The slow-hardening mortar also contributed to these deformation which probably because the whole original church was built in reckless speed within five years and ten months.13 On the other hand, more than two-thirds time of the time taken to construct the entire church was used by Isidore the Younger for the replacement of the dome which suggests that he designed the dome with greater care compared to his uncle.14 The dome built by him has now survived for more than 1,400 years.15

Fig. 8. The exterior forms of the multiple domes of Hagia Sophia. (Drawing by Rowland Mainstone, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 103.)

Despite the collapse of parts of the building, Hagia Sophia was still indeed in every sense of the word, a true architectural wonder. The edifice challenged new possibilities in architecture and was considered as one of the most significant and influential buildings in history. The advanced structural system that allowed the dome to rest by only four piers and the innovation of pendentive to complete the system benefitted the latter architect in terms of planning options and structural design.

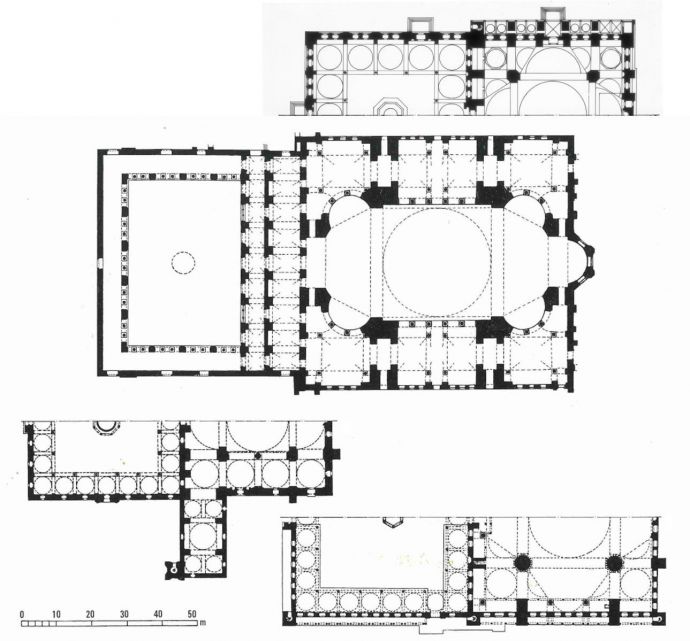

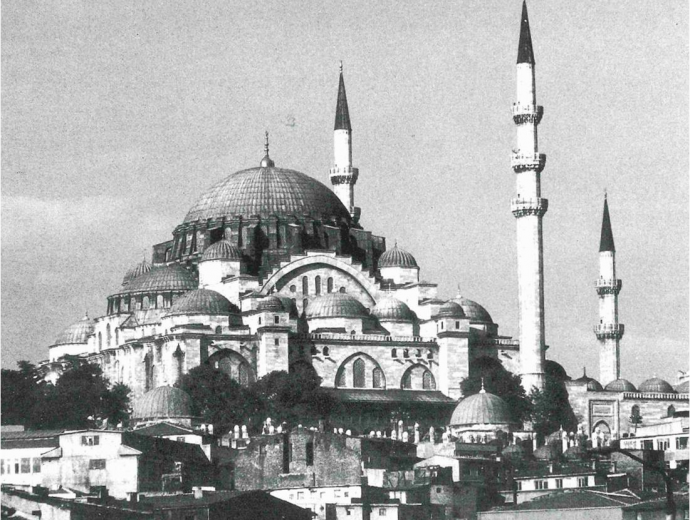

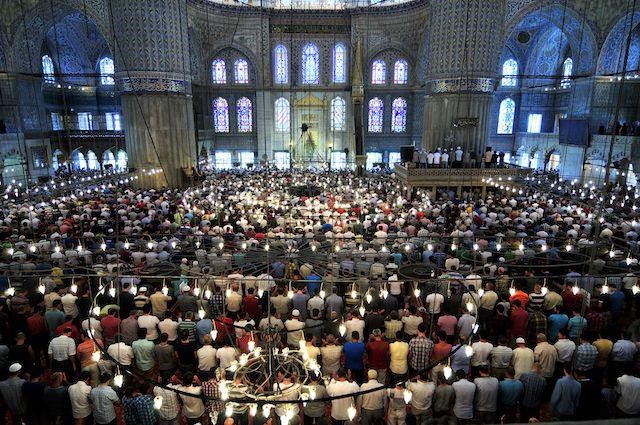

This great church was not only becoming a significant archetype of the church in its own day, but also the design of the mosques during Ottoman period after the fall of Constantinople. The Justinian’s church was then converted to become the first principal mosque in 1453.16 Perhaps due to its unique feature of vast and unobstructed central interior space of the ‘nave’ was pertinent to Muslim’s way of prayer which strongly influenced the design and planning of the new mosques during Ottoman occupation that mimicked Hagia Sophia.

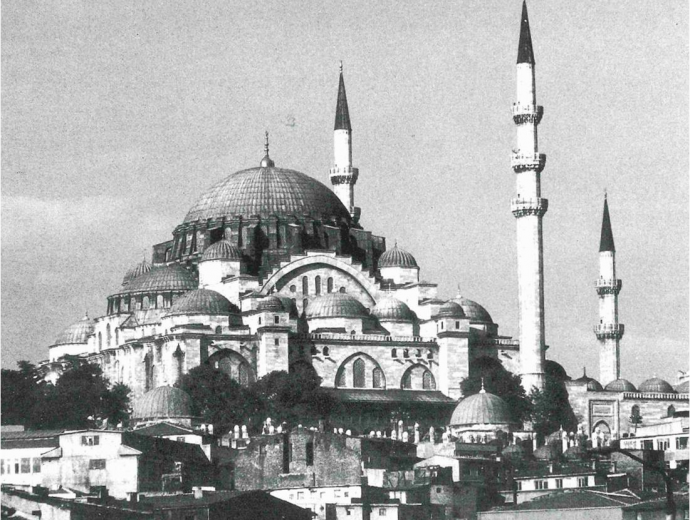

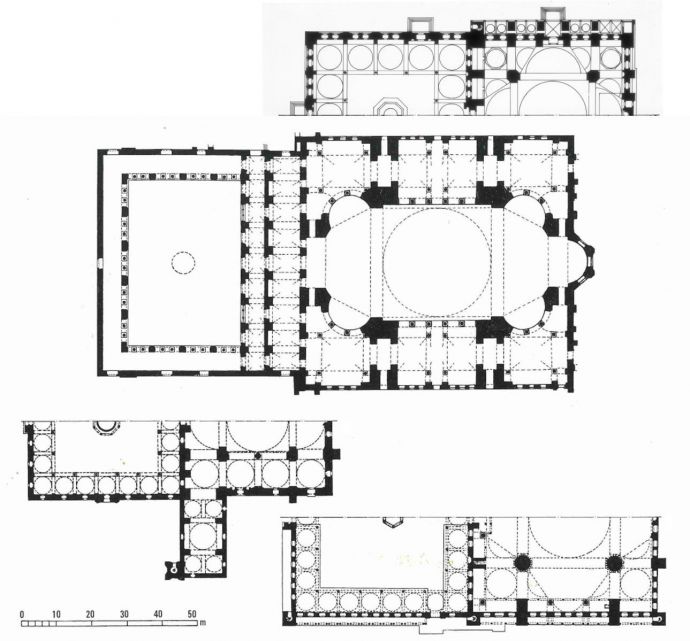

Fig. 9. Floor plan comparison between Hagia Sophia (centre), the Sehzade Mosque (top right), Beyazit Mosque (bottom left) and Suleymaniye Mosque (bottom right). (Drawing by Rowland Mainstone, in Mainstone,” Hagia Sophia,” 250.)

Fair resemblance can be seen in Beyazit mosque which was completed around the 1500s. Some essence of the Hagia Sophia can be traced here – the placement of central dome and the similar use of semidomes to expand the interior space underneath it. Although only two semidomes were placed, one facing Mecca and the other placed at the entrance with a similar principal of vaulting system in Hagia Sophia. Yet unlike Hagia Sophia, there is no smaller semidomes around the main one. The triangular pendentive then was used to bound these two semidomes that were placed at the corner of the square base.

The preponderant influence of Hagia Sophia became clearer in the buildings erected by Sinan and his successors. The most significant mosques he built for Suleyman were the the Sehzade and the Suleymaniye. The former mosque, the Sehzade was built slightly earlier than the latter. It was the first imperial mosque to have the cluster of semidome feature like in Hagia Sophia, smaller semidomes adjoined to the bigger semidomes. The difference to Hagia Sophia was Sinan’s intention to make further expansion to the main central space by putting a further large semidome bays flanked to each side of the main central dome corresponding to the main axis.17 This reinforced the centralizing tendency of expanded multiple domes and semidome structures.

Lastly, Suleymaniye Mosque, the one that has the strongest influence from Hagia Sophia in terms of scale, planning and structural system. There were two semidomes located similar to the Beyazit Mosque, at the entrance side and at the side facing Mecca with a main central dome. The akin rising semidomes in Hagia Sophia was placed on to the building and adjoined to the main semidome with one extra bay flanking the dome on each side.

Fig. 10. Occupation of central space during prayer time. (Photograph by Blue Mosque, accessed http://www.bluemosque.co/prayer-times.html.)

Fig. 11. The heavenly dome of Hagia Sophia. (Photograph by Tahsin Aydogmus. Hagia Sophia, in Kleinbauer,” Hagia Sophia,” 82.)

One cannot simply say how strong Hagia Sophia has influenced the structural design of mosques during Ottoman era. There is no evidence of direct copying of the construction techniques and there were always further developments for every building depending on the intention of the designer. Dissimilar motives of architectural expressions resulted in a different outcome or form for each structural element. In the case of the Byzantine church and the Ottoman mosque, the difference is of course in terms of religion and belief. In the church, the dome was mainly designed to express the symbolism of Heaven, ergo emphasizing the superiority of the dome.18 Howbeit, in the mosque, the planning of domes emphasized more on the notion of Islamic type of prayer where the expansion were always on the side facing Mecca and the unobstructed central space. However, it is clear that the construction of Hagia Sophia has been closely examined by other designers for them to learn the lesson from the failure and success based on their own merit and perspective.

From Procopius eyewitness perspective of 500th BC till today, Hagia Sophia never fails to affect the beholder. Its building fabric indeed referenced endless localities and daring audacities. Ultimately, it created a fascinating adventure and lessons for the beholders to see, listen and learn.

Words count: 2498 including footnotes, captions and references.

1 W. Eugene Kleinbauer et al., Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey: Scala Yayıncılık, 2011), 44.

2 Nigel Hiscock, The Symbol at Your Door: Number and Geometry in Religious Architecture of the Greek and Latin Middle Ages (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007), 69.

3 Rabun Taylor, "A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian's Hagia Sophia,Constantinople," 96

4 W. Eugene Kleinbauer et al., Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey: Scala Yayıncılık, 2011), 29.

5 Rabun Taylor, "A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian's Hagia Sophia,Constantinople," 96.

6 Rowland J. Mainstone, Hagia Sophia (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 162.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Rabun Taylor, "A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian's Hagia Sophia,Constantinople," 96.

10 Rowland J. Mainstone, Hagia Sophia (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 173.

11 Ibid, 165.

12 Rabun Taylor, "A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian's Hagia Sophia, Constantinople," 73.

13 Emerson and Van Nice, "Hagia Sophia: The Collapse of The First Dome," 95.

14 W. Eugene Kleinbauer et al., Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey: Scala Yayıncılık, 2011), 29.

15 Rabun Taylor, "A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian's Hagia Sophia, Constantinople," 96.

16 Robert S. Nelson, Hagia Sophia, 1850-1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 1.

17 Rowland J. Mainstone, Hagia Sophia (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), 253.

18 Nigel Hiscock, The Symbol at Your Door: Number and Geometry in Religious Architecture of the Greek and Latin Middle Ages (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007), 66.

Bibliography

Books

- Hiscock, Nigel. The Symbol at Your Door: Number and Geometry in Religious Architecture of the Greek and Latin Middle Ages. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007.

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene, Antony White, Henry Matthews, and Tahsin Aydoğmuş. Hagia Sophia. Istanbul, Turkey: Scala Yayıncılık,

- Mainstone, Rowland J. Hagia Sophia. London: Thames and Hudson,

- Mango, Cyril A. The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453: Sources and Documents. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

-

Nelson, Robert S. Hagia Sophia, 1850-1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Journal

- Van Nice and Emerson William. "Hagia Sophia: The collapse of the first dome." Archaelogy 4, no. 2 (1951): 94-103.

- Taylor, Rabun. “A Literary and Structural Analysis of the First Dome on Justinian’s Hagia Sophia, Constantinople.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 1 (1996): 66-78.

Website

- Blue Mosque. "Prayer Time." Accessed September 30, 2018. http://www.bluemosque.co/prayer-times.html.