AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

View the papers that match the selected criteria.

Title: Fijian Bure Kalou

|

Copyright: Zachary Low

|

Description: What are the cultural, technological and site influences that critically-inform our understanding of [your selected building or building type or building complex]?

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

Fijian Bure Kalou

|

What are the cultural, technological and site influences that critically inform our understanding of the Fijian Bure Kalou?

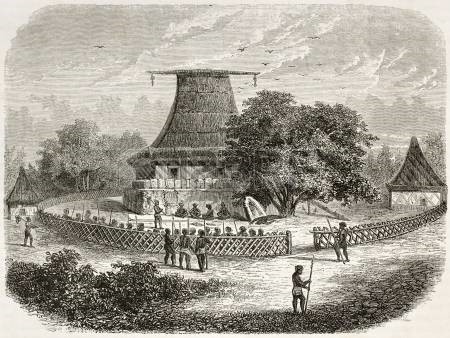

Bure Kalou or Gods House (Bure meaning house and Kalou meaning spirit)[1] is the name prescribed to indigenous Fijian churches taking the form of a plain rectangular high gabled thatched roof structure lacking internal partitions with a single opening acting as a door[2]. In these churches the village Bete (Priest) would live, religious offerings of magiti (food) and Iyau (valuable goods) would occur and where the Village Bete (Priest) and Turaga (Village Chief) would contact Kalou Ou (God) (Kalou meaning Spirit and Ou meaning origin ie Original Spirit)[3]. The Fijian Bure Kalou is a complex building type that is the amalgamation of various cultural, technological, site-specific factors, emerging technologies and new materials that amount in a captivating end result. Through analysis and interrogation of these factors we can achieve a deeper understanding and appreciation for both the form and function of how the Fijian Bure Kalou came to be. Painting of a Bure Kalou in context of a standard Fijian Village1

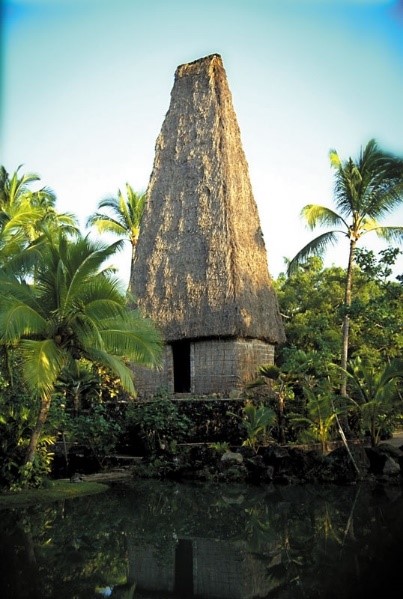

Prior to the arrival and colonisation by European settlers in Fiji around the 1860’s[4] Bure Kalou were considered one of if not the most important structures in almost every Fijian village.[5] The most commonly used materials to construct Bure Kalou were timber and straw that were either tied or packed together. They had dirt or clay floors topped with coconut leaves. These materials were placed a top of a yavu (raised earth foundation) with a surrounding tuvatuva (stone wall).[6] The Bure Kalou would be constructed by the local men under the watch and direction of the village mataisau (Equivalent of architect or designer) using techniques passed down from generation to generation[7]. Notably, the location of the village would play a defining role in the materials used in construction of the Bure Kalou as villages would have to source materials from areas within relatively close proximity of them[8]. For example, Bamboo trees are available in abundance in the highlands or Viti Levu as such most houses in that area consist of bamboo[9]. Bure Kalou reigned prominent throughout Fiji for a very long time however this would change once European settlers began to convert indigenous Fijian people to Christianity sometime around the 1860’s[10]. Because of this many Bure Kalou were demolished and replaced with somewhat traditionally western Churches[11]. Few original Bure Kalou are still standing. This is a replica2

The majority of the Fijian Bure Kalou’s design can be easily attributed to the Fijian cultural context they were designed for and constructed in. This holds true for both the interior and exterior as well as the form and the function. The Bure Kalou was consistently the tallest structure within any Fijian village. It absolutely towered over every other building in the village and was placed within the centre making it the centre piece and utmost important building in the village complex[12]. This was in no way coincidental and occurred due to the extremely strong cultural focus of the Indigenous Fijian people. The Indigenous Fijian people held extremely strong faith and beliefs within their gods and believed that the higher they reached into the sky the closer they would be to Kalou Ou (God)[13]. As such the Bure Kalou is designed to stretch as high into the sky as their structural technology would allow them to. Whilst every Bure Kalou would be unique to its own village they generally stood at around 6 stories high however only consisting of a single floor[14].

Pencil sketch shows scale relative to Chiefs house (right) The exterior was plain without any openings or windows bar a single unprotected opening acting as a door. This lack of a closing door or any form of screen over the entrance was an intentional design decision based upon the Indigenous Fijians extremely open culture. A clear line of privacy for Indigenous Fijians was never truly considered a big deal and this reflects not only in the Bure Kalou but in all structures within the Indigenous Fijian village with all structures being fully accessible[15]. The influences of indigenous Fijian culture and religion hold true in all regards all the way down to the roots of the construction. Given the obvious dangers of working on such a large-scale structure it was common for workers to die from accidents or injuries. If a worker died they would be buried directly into the site beneath the foundation to help increase the stability of the construction. Culturally this was seen as an offering to Kalou Ou (God) with the hopes that the spirit of the deceased would request that Kalou Ou oversee the project to a fruitful end.[16] The interior of the Bure Kalou Featured an extravagantly long white masi (tappa or bark cloth) spanning the entire vertical distance of roof all the way down to the floor. This cloth acted as a bridge between the Bete (Priest) and the sky where the gods and spirits dwelled essentially making the Priest a conduit between the two realms.[17] The priest was the voice of God on earth and would give advice and preach based on what he was told through his time being connected through the masi cloth bridge. This ritual of connection to Kalou Ou would commence under the influence of the hallucinogenic plant kava that had been ground into a drinkable form.[18]

Given that the indigenous Fijian people literally lived and died by the voice of the Turaga (Chief)[19] and the chief consulted the Gods via the Bete (Priest) for direction especially during times of hardship such as drought or food deficiencies[20] it is clear that the Bure Kalou was vital to the indigenous Fijian people, it was ultimately what dictated their flow of life and the decisions they were to live by.

Whilst it is unclear as to when the technologies such as the wooden supports used to construct Bure Kalous first originated from due to a lack of historical documentation prior to the arrival of European settlers a clear line of development can be made through comparison of standard Fijian Bures (typically homes) and Bure Kalous. Structurally it can be said that the Bure Kalou is just a much more extravagant rendition of the standard Fijian Bure in relation to the overall scale[21] however the aspects resulting in the make up of the Bure Kalou all had to be strengthened to accommodate for the increase in scale[22]. Developments within these fields occurred through generations of development as methods of fabrication and assemblage were passed down from generation to generation of mataisau (equivalent of architect)[23]. Photograph showing technical detailing4

The materiality of the Bure Kalou were as stated earlier dependant on what materials were available within close proximity[24] of the village given that little to no information exists on what earlier renditions of Bure Kalou were composed of we can’t be entirely sure as to what materials could be considered as being new or inventive for them. That said Bure Kalou were generally made using hard solid woods as posts, walls were made using leaf hatchings or bamboo reeds, bamboo or other hard poles as rafters, beams using whatever light timbers which were locally available and roofs out of Fijian asparagus (duruka), sugar cane leaves (dovu), coconut and palm leaves (soga) and reeds (gasau)[25]. As stated earlier due to the lack of documented history it is very hard to determine just how many of these materials can actually be considered as new or change inducing to the way indigenous Fijians constructed their structures. That said the development of the Bure Kalou Most definitely caused a in the development of the traditional Fijian religion allowing for further ways to make contact with and undertake the actions of Kalou Ou (God)[26] Pencil sketch showing the raised earth base5

Both the built and natural landscape also played roles in the development and placement of the Bure Kalou. The Bure Kalous primary and most important purpose was to act as a bridge between the spirit realm and that of the living by piercing the sky, therefore the higher the structure stood the stronger the connection[27]. Whilst the limitations of structural stability kept the Bure Kalou below a certain height[28] the land beneath could be manipulated to further raise the overall height of the Bure Kalou and as such areas of high altitude such as natural hills or areas in which land could easily be manipulated and stacked were preferred for development of new Bure Kalou[29]. The earth works beneath the structure itself would be raised to give significant increases in height to the Bure Kalou allowing it to further stretch into the sky forming and even stronger link to the spirit realm and as such Kalou Ou (God)[30]

Built landscapes also informed design decisions based on the placement of the Bure Kalou. As stated earlier the Bure Kalou was the most important structure in the Fijian village due to strong religious beliefs and sense of direction attained from Gods[31]. Therefore, the location of the Bure Kalou would always be informed by the surrounding village structures as to ensure that it would always be centrally located and in close relation to the Vale Levu (“Big House” or Chiefs house)[32] signifying how the whole village was based upon and followed the word of Kalou Ou (God)[33]. The fact that the Bure Kalou took priority over the Vale Levu[34] as the centre piece of the village further highlights just how significant it was. Ultimately through the analysis and interrogation of the Cultural, Technological, Materialistic and site-specific factors that amalgamate to create the indigenous Fijian Church or Bure Kalou we can understand and begin to feel just how it was that the form and functionality of the church came to be even though we do not know just how long these designs took to manifest. Its is the coalition of both culture and structure that led us to what is an all-round interesting form, weather this fascination comes from the sacred rituals that the form of the Bure Kalou accommodate so greatly for or the monumental structure that further strengthened the peoples close bond with God it is truly safe to say that the indigenous Fijian Bure Kalou was a critical and culturally significant form of architecture to the Fijian people that stands testament to a time long past. Final Word Count – 1683

Bibliography Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). ARISI VUNIDILO, "Reviving Fijis Traditional Architecture," Thecoconet, , accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.thecoconet.tv/coco-talanoa/guest-writer/reviving-fijis-traditional-architecture/. France, Peter. The Charter of the Land; Custom and Colonization in Fiji. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1969. John H. Shaver, "The Evolution of Stratification in Fijian Ritual Participation," Religion, Brain & Behavior, 101st ser., 5:2, no. 117 (March 20, 2014): , doi:10.1080/2153599X.2014.893253. Jones, Nina. "Bure Kalou, the Fijian Spirit House." Polynesia.com. January 15, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.polynesia.com/blog/bure-kalou-the-fijian-spirit-house/. KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 1303-1313, 81, no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. Parke, Aubrey. "Navatanitawake Ceremonial Mound, Bau, Fiji: Some Results of 1970 Investigations." Archaeology in Oceania33, no. 1 (1998): 20-27. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1998.tb00396.x. Parke, Aubrey L. "The Waimaro Carved Human Figures:Various Aspects of Symbolism of Unity and Identification of Fijian Polities." The Journal of Pacific History32, no. 2 (1997): 209-16. doi:10.1080/00223349708572839. Unknown Author. "Bure Kalou (model Spirit House)." Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/206948.

Illustrations in order of Appearance

[1] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [2] KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 1303-1313, 81, no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. [3] Parke, Aubrey. "Navatanitawake Ceremonial Mound, Bau, Fiji: Some Results of 1970 Investigations." Archaeology in Oceania33, no. 1 (1998): 20-27. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1998.tb00396.x. [4] France, Peter. The Charter of the Land; Custom and Colonization in Fiji. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1969. [5] Jones, Nina. "Bure Kalou, the Fijian Spirit House." Polynesia.com. January 15, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.polynesia.com/blog/bure-kalou-the-fijian-spirit-house/. [6] KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 1303-1313, 81, no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. [7] ARISI VUNIDILO, "Reviving Fijis Traditional Architecture," Thecoconet, , accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.thecoconet.tv/coco-talanoa/guest-writer/reviving-fijis-traditional-architecture/.

[8] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [9] Ibid [10] France, Peter. The Charter of the Land; Custom and Colonization in Fiji. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1969. [11] ARISI VUNIDILO, "Reviving Fijis Traditional Architecture," Thecoconet, , accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.thecoconet.tv/coco-talanoa/guest-writer/reviving-fijis-traditional-architecture/. [12] Parke, Aubrey L. "The Waimaro Carved Human Figures:Various Aspects of Symbolism of Unity and Identification of Fijian Polities." The Journal of Pacific History32, no. 2 (1997): 209-16. doi:10.1080/00223349708572839. [13] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [14] Jones, Nina. "Bure Kalou, the Fijian Spirit House." Polynesia.com. January 15, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.polynesia.com/blog/bure-kalou-the-fijian-spirit-house/. [15] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [16] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [17] Parke, Aubrey L. "The Waimaro Carved Human Figures:Various Aspects of Symbolism of Unity and Identification of Fijian Polities." The Journal of Pacific History32, no. 2 (1997): 209-16. doi:10.1080/00223349708572839. [18] Ibid [19] John H. Shaver, "The Evolution of Stratification in Fijian Ritual Participation," Religion, Brain & Behavior, 101st ser., 5:2, no. 117 (March 20, 2014): , doi:10.1080/2153599X.2014.893253. [20] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [21] KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) , no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. [22] Ibid [23] ARISI VUNIDILO, "Reviving Fijis Traditional Architecture," Thecoconet, , accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.thecoconet.tv/coco-talanoa/guest-writer/reviving-fijis-traditional-architecture/.

[24] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [25] KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 1303-1313, 81, no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. [26] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [27] Parke, Aubrey L. "The Waimaro Carved Human Figures:Various Aspects of Symbolism of Unity and Identification of Fijian Polities." The Journal of Pacific History32, no. 2 (1997): 209-16. doi:10.1080/00223349708572839. [28] KOBAYASHI, Hirohide, and Ayako FUJIEDA. "RESEARCH ON INDIGENOUS BUILDING TECHNOLOGY OF FIJIAN TRADITIONAL WOODEN HOUSE - BURE." Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), no. 724 (June 16, 2016). doi:https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.81.1303. [29] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [30] Ibid [31] Asesela D. Ravuvu, The Fijian Way of Life (Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 1983). [32] Unknown Author. "Bure Kalou (model Spirit House)." Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/206948. [33] Jones, Nina. "Bure Kalou, the Fijian Spirit House." Polynesia.com. January 15, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.polynesia.com/blog/bure-kalou-the-fijian-spirit-house/. [34] ARISI VUNIDILO, "Reviving Fijis Traditional Architecture," Thecoconet, , accessed April 10, 2018, http://www.thecoconet.tv/coco-talanoa/guest-writer/reviving-fijis-traditional-architecture/.

|